There is only one Asian shipbuilding tradition that utilizes planks with carved lugs. The Lingga Wreck is a Southeast Asian lashed-lug ship.

A pioneer in the study of lashed-lug design, Pierre-Yves Manguin (1996: 184), notes that all pre-14th century Southeast Asia ships found in archaeological contexts belong to this technical tradition. The earliest known example was found on a river bank in Pontian, West Malaysia. Radiocarbon dating indicates a 3rd to 5th century CE date. Ship’s timbers dated from the 5th to the 7th century have been excavated at Kolam Pinisi in Sumatra. Also in Sumatra, near the Musi River, lashed-lug vessel remains have been radiocarbon dated to the 7th or 8th century, although ceramics in the vicinity are a 10th century product. A remarkably intact lashed-lug ship has been discovered on an ancient beach ridge near the town of Punjulharjo in northern-central Java (Manguin forthcoming). Radiocarbon analysis of the ijok rope used to tie her strakes together yielded a late 7th to late 8th century date. Several medium sized lashed-lug vessels, perhaps intended for inter-island trade or for battle, have been unearthed near Butuan in Mindanao, the Philippines. Timbers from five of the boats provide radiocarbon dates between the late 8th and the late 10th century. In northern Sumatra, near the city of Medan, many lashed-lug timbers, some paddles and a wooden anchor were exposed during sand mining. The site would seem to have been an ancient harbour that served the settlement of Kota Cina from the 12th to the 14th centuries.

These examples are all from terrestrial sites. They are not shipwrecks at all but abandoned hulls that have gradually been covered with sediment in rivers or estuaries over centuries of geological change. As such, they were generally not carrying any cargo or personal belongings, so it is difficult to draw conclusions on the original function of these vessels.

In recent years some spectacular finds have been made underwater, all associated with full cargoes. The 10th century Intan Wreck (Flecker 2002) was voyaging from Sumatra to Java with an extremely diverse cargo of metals, ceramics, bronze statuary, glassware, jewellery and many other trade goods when it went down in the Java Sea. Only fragments of the hull remained, but they were enough to confirm lashed-lug construction. Another ship of the same era carrying the same diverse, but much larger cargo, and trading on the same route, wrecked in deep water to the north of Cirebon, Java. The Cirebon Wreck (Liebner 2014) survived largely intact and provides an incredible amount of detail on lashed-lug construction. Recently another lashed-lug ship was discovered off Sabah, East Malaysia. The Flying Fish Wreck (Flecker forthcoming) was carrying a cargo of iron and Fujian ceramics, including unique Cizao dishes painted with soaring flying fish. She was voyaging from Quanzhou in China to Brunei or Santubong in Sarawak during the early 12th century. The Java Sea Wreck (Flecker 2003; Mathers & Flecker 1997) was another fragmentary discovery, lying less than 10 miles from the Intan Wreck in the Java Sea. She had made the voyage to China and was returning with a huge cargo of Fujian ceramics and ironware when she sank in the 13th century. Chronologically, the most recent lashed-lug ship is the c.1300 Jade Dragon Wreck (Flecker 2012), another find off Sabah. She was voyaging from Wenzhou in China to Brunei or Santubong with an almost exclusive cargo of Longquan celadon.

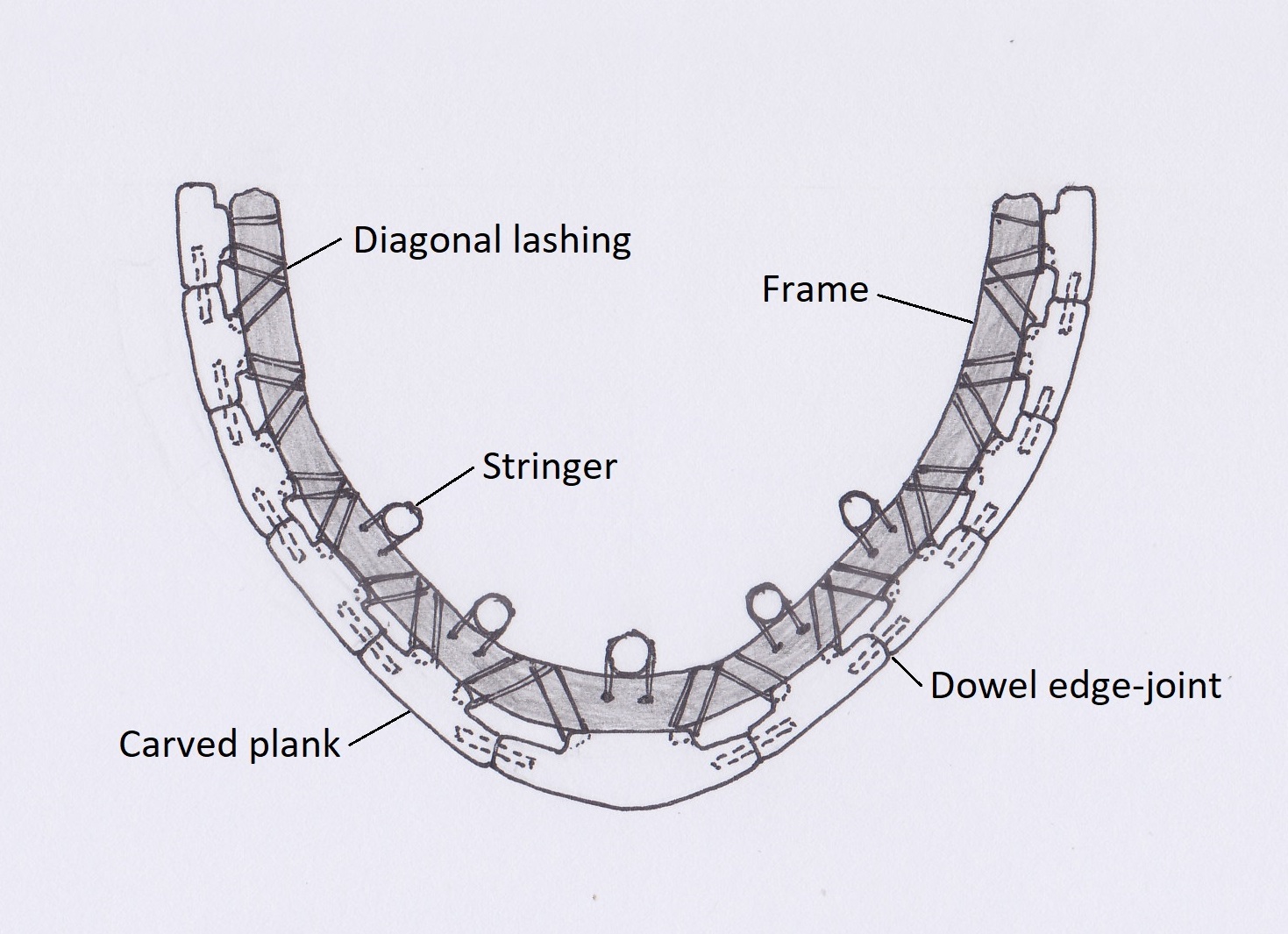

Lashed-lug ships were built by raising planks on each side of a keel piece that shows clear signs of having evolved from a dug-out base. The planks are edge-joined with wooden dowels, which in earlier examples are interspersed with internal stitching. Vegetal fibre stitches usually occur in pairs within the seam, not being visible from outside the hull. Over the centuries the number of dowels increased while the stitching decreased until the latter was eventually eliminated altogether, around the 9th or 10th century.

The planks are carved, rather than bent to shape, and incorporate protruding lugs, locally termed tambuku. Typically, a tree trunk is split lengthways with only one plank being made from each half. Holes are carved or drilled out of the lugs so that they may be lashed to frames and/or thwart beams. Apart from maintaining the cross-sectional shape of the vessel, the frames provide shear and bending strength to reinforce the wooden dowels within the planks. Lashings between lugs and over the frames serve to hold the frames in place and to pull the planks together. Tiers of thwart-beams, lodged above or below the lugs, contribute to the compressive forces that hold the planks tightly together despite the flexing of the hull. They also help to provide lateral support, preventing the hull from opening up or bending inwards.

On first impression a lashed-lug boat appears to be flimsy, suitable perhaps for fishing or coastal transport. But from archaeological evidence ships of up to 35 m were constructed by this technique, and Chinese historical sources indicate that some may have been as large as 45 m (Manguin 1996: 188; forthcoming). The secret to their success may lie in their flexibility. The vegetal bindings, both the plank stitching and the lug and thwart ties, are to some degree elastic. As the vessel flexes with the waves the bindings stretch but always maintain their tensile properties, thereby keeping the planks in compression and the boat relatively watertight. Vessels constructed with nails and bolts, on the other hand, must be rigid and therefore utilise more and bigger timbers. Once such a vessel starts flexing the fastenings tend to loosen as the holes are enlarged, and the compressive forces holding the ship together decrease, resulting in a loss of watertight integrity. Overall, the lashed-lug construction technique can be viewed as a magnificent piece of engineering. Great compressive forces were achieved in a light structure utilising cheap and readily available materials.

These early Southeast Asian craft were steered by two quarter rudders, a system that survives to this day on many sailing vessels still plying the waters of Indonesia, the pinisi being a fine example. They were rigged with up to four tripod masts and a bowsprit and used canted square or lug sails.

Identification of timber species may have been useful in definitively determining where in Southeast Asia the Lingga ship was made, but this has not been attempted to date. Species such as teak and meranti have been used for frames and planking on other lashed-lug ships. Neither of these is uniformly distributed throughout Southeast Asia, so they may provide clues on provenance. Dowels are almost always of belian, or Borneo ironwood, although the light reddish shade of the Lingga dowels is not indicative of this timber. The lashing material is almost always ijok, or sugar palm fibre, which is consistent with the appearance of the Lingga lashings. The Flying Fish Wreck, unusually, utilised both ijok and an unidentified rattan-like binding.

Irrespective of timber species, with a Chinese cargo obviously bound for an Indonesian port, the Lingga Wreck is most likely to have been an Indonesian-made vessel. The ship was probably homeward-bound after delivering a cargo of jungle and sea products and prized spices to China.