5. The Wider Significance of the Site

Buried under the shores of today's Singapore River are the remains of a much older civilisation. Indeed, the EMP excavation, like many digs of recent years, adds another piece to the archaeological puzzle. It is clear from the abundance of 14th-century artefacts that the site forms an integral part of the Temasek settlement. The largest collection of pre-modern artefacts recovered on land, the yield reflects how busy this area near the original entrance of the river must have been in ancient times.

While the provisional understanding of the assemblage appears not unusual for a Temasek site, it is crucial to examine its wider context and how certain aspects of it are evidenced by the archaeological features that interdigitate the site. When compared with the 1998 EMP excavation (Miksic 2013: 245–252), the 100-metre proximity of the two sites represents an important area between the intertidal mark and the upper riverbank respectively. Conceptually speaking (Ford 2011b; Rainbird 2007), this is the liminal space that marks the transition between land and water and more significantly, the place where seafarers and objects start or end their voyage.

For thousands of years, despite its danger, the sea remains a place of mystery, knowledge, and opportunity. Regardless of geography and beliefs, this enigmatic and almost universal attraction meant that the mental and physical topography of the coast dwells deeply and meaningfully within most maritime societies whose perspectives at times can be constrained by limitations in traditional archaeology.

Maritime archaeology recognises the contiguity of the coast between maritime-land sites and underwater sites. In consideration of this, Temasek is physically defined not only by terrestrial sites, but also by its harbour, geography, geology, landmarks, marine biodiversity, and shipwreck sites. There are also intangible aspects (see, for example, Westerdahl 1992) that remain unexplored. In this case, excavations in or near waterlogged urban areas such as EMP are challenging but important, because the heavily trafficked site can potentially tell us more about the character of the port and how it functioned. What makes this site significant and unique are the remains of port-related features that were, regrettably, excavated and documented very quickly.

Interestingly, a large amount of rocks of relatively similar scale (Figure 35) were found—densely associated at times—throughout the main excavation area. It thus formed a feature (Figure 36) that was straddled by earlier and more recent deposition of artefacts (refer to Figure 32). Although the belated discovery of this feature means that it was not entirely documented, it is apparent to archaeologists that the occurrence of these rocks is unnatural. It is plausible that if some of these were not abandoned ship ballasts, they may have been a foundation of sorts for roadways, timber-and-thatch structures, or even a pier. The use of rocks as a foundational substrate would not have been uncommon at that time and can be found, for example, in Johor Lama and Trawas (east Java). It is also possible that these sandstone rocks were obtainable on the opposite side of the Singapore River mouth, in an area called Rocky Point by the British in 1819. This was also where the Singapore Stone stood originally.

Intriguingly, the depth of this feature coincides with the layer containing the highest volume of 14th-century artefacts (150 CMBD to 170 CMBD). This suggests that the feature is associated with a time when Temasek was most active as a port. The horizontal distribution of rocks in this layer goes beyond the main excavation area and its occurrence represents an important aspect of Temasek that is not previously documented.

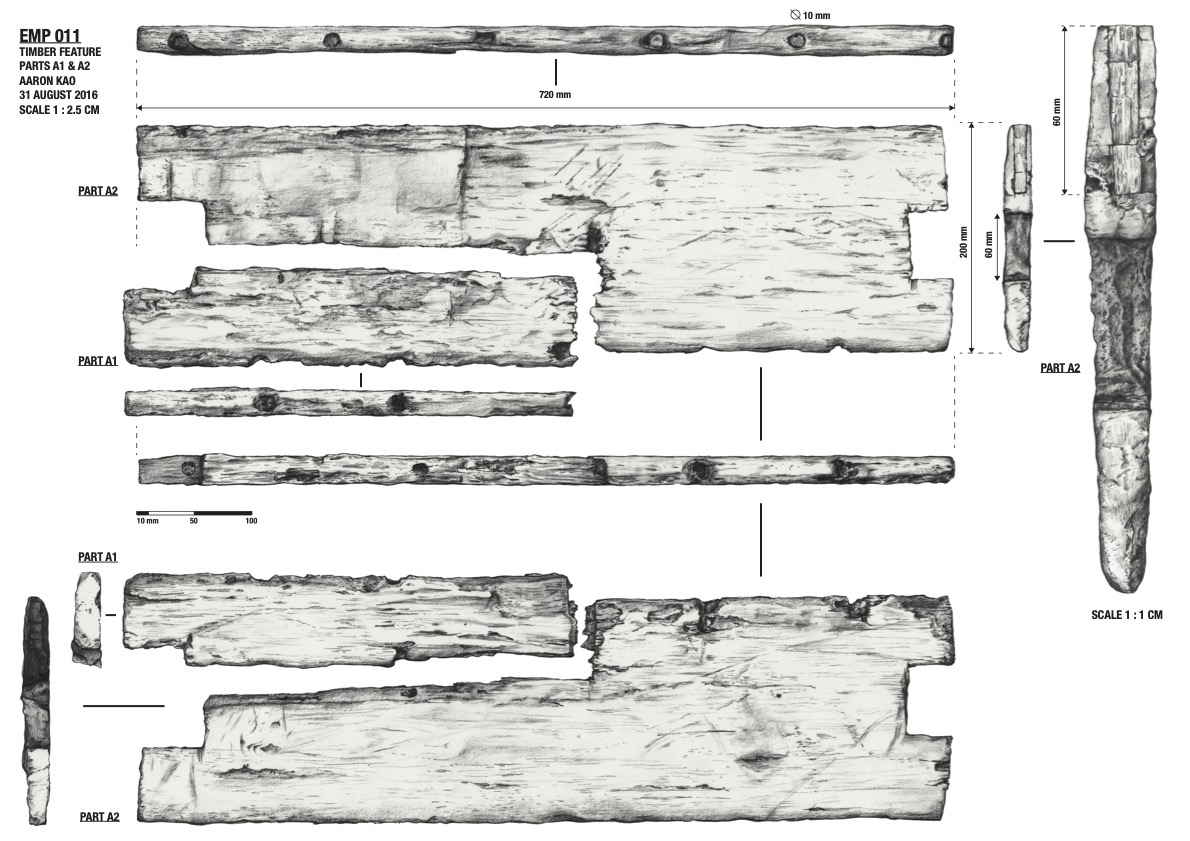

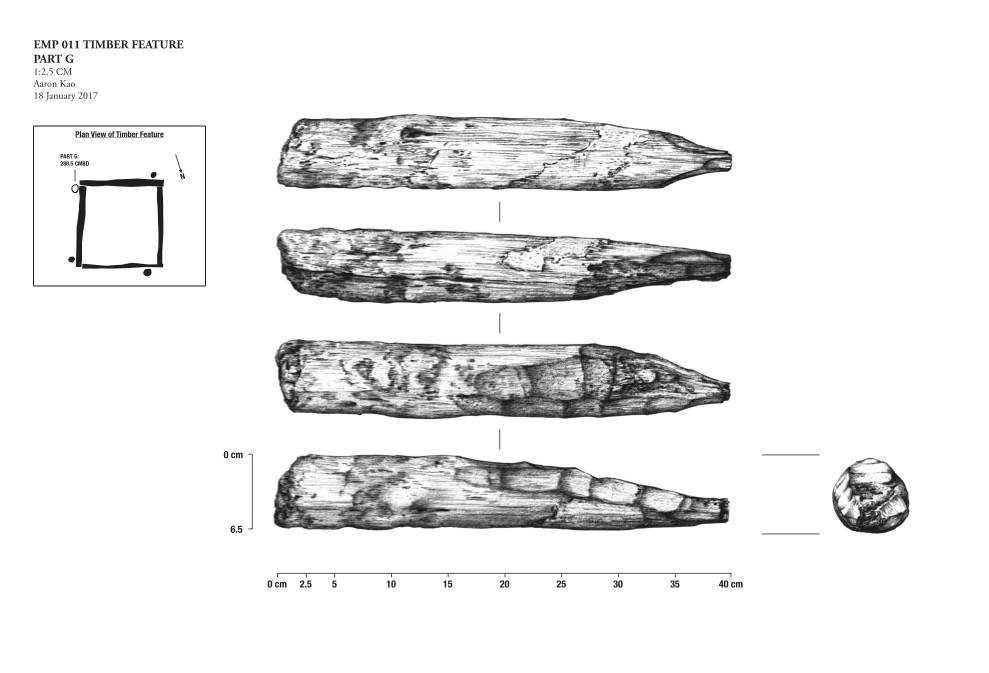

Preserved at the same time in waterlogged anaerobic soil is a pair of timber boxes (Figure 37) with similar dimensions and construction, both significant burial depth. Interestingly, some of the planks exhibit dowel-edge-joints used in traditional Southeast Asian boatbuilding (Figure 39). The four-sided metre-square boxes were held in the ground by simple box joints and vertically driven wooden pegs (Figure 39). Despite the fact that their function remains unknown, it is clear that good quality timber was repurposed from run-down boats for these boxes. The repetition and spacing of the features indicate that they were not random but, like the rock feature, they may have been of economic use. It is possible that more of these as well as other features remain buried nearby.

The boat planks represent the first ever fragments of a ship-on-land wreck (see, for example, Delgado 2012) in Singapore. Its multiple contexts suggest that, while it is yet unclear whether there was boatbuilding nearby, disused vessels were certainly dismantled. Although the timber features are not found within the sampled units of this report, their presentation and discussion are necessary for site context. Notable at the same time is the fact that archaeological features of similar nature were not found in nearby digs, or were perhaps disregarded or unintentionally missed. The presence of 16th-17th-century porcelain confirms that the site was not entirely abandoned after its century-long reign and that the careful analyses of each arbitrary layer, hypothetically speaking, may nuance the little-known chronological subtleties of pre-modern Singapore. This period remains understudied.

Also, in terms of the more recent colonial period, it is unfortunate that the excavation was situated in the midst of construction work and had to be excavated expeditiously. What was clearly an overlying colonial stratum was not excavated and documented by archaeologists.