For a detailed report on the Temasek Wreck, covering the discovery, survey, excavation, cleaning and conservation, wrecking process, artefact overview, Temasek parallels, dating, likely vessel type, likely port of lading, and likely destination, refer to “The Temasek Wreck (Mid-14th Century), Singapore: Preliminary Report”.

The Temasek Wreck Blue-and-White Porcelain Database: Distribution and Composition

By Dr Michael Flecker

Introduction

The Temasek Wreck was lost in Singapore waters. She was progressively excavated from 2016 until 2019 by the Archaeological Unit of the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, acting on behalf of the National Heritage Board.

Her surviving cargo of Chinese ceramics comprised blue-and-white, qingbai and shufu porcelain from the kilns of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province; Longquan celadon from Zhejiang Province; stoneware from Cizao in Fujian Province; greenware that was probably also from Fujian kilns, and Dehua whiteware. The very few non-ceramic artefacts included glass beads, gold foil, wrought iron, lead ingots, and a few degraded copper-alloy objects. All organic cargo rotted away long ago, as did the entire ship's structure. Without any hull remains it is impossible to conclusively identify the type of ship. However, from circumstantial evidence such as an exclusive Chinese cargo and an absence of non-Chinese artefacts, there is a high probability that the ship was a Chinese junk.

Notably, the Temasek Wreck contains more Yuan blue-and-white porcelain than any other documented shipwreck in the world. Over 2,350 shards along with a handful of intact or nearly intact objects, have been documented. The total weight is approximately 136 kg. In comparison, the Binh Chau Wreck, a Chinese junk lost in Vietnam, contained a handful of Yuan blue-and-white bowls, cups, dishes, and covers. Only 103 blue-and-white shards were recovered from the Shiyu 2 Wreck 1, which was lost in the Paracels, although the site was looted before official excavation. A mere nineteen large shards were recovered from an undocumented wreck in the Red Sea,2 and another rumoured site near Jeddah yielded even fewer pieces. 3 Just one Yuan blue-and-white jar was lifted from a possible wreck off Samar in the Philippines.4

While the mass production of the other ceramic types found on the wreck was well established prior to the 14th century, blue-and-white porcelain was not produced in quantity until around 1330. It was a new creation that immediately found favour both in China and internationally. The resultant extensive distribution throughout Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East and the Maghreb belies a very short production period, which is thought to have been terminated, or at least largely curtailed, in 1352 with the invasion of the Red Turban Army.5 An analysis of the motifs on the blue-and-white porcelain from the Temasek Wreck strongly suggests that their earliest production date is 1340, resulting in a wreck date range of only 12 years. The most conservative range is from 1330, the approximate date of first production, to 1371 when the first Ming Emperor, Hongwu, banned overseas trade.

It is rare that a shipwreck with no historical documentation, and no specifically datable artefacts, can be dated as precisely as this, even on the more conservative level. Once a detailed analysis of the many ceramic types and designs is undertaken, an equally rare event may occur: the Temasek Wreck finds, which mark one moment in history, may contribute to the accurate dating of Yuan ceramics.

From the location of the wreck, the many parallel finds, and importantly a common dearth of large blue-and-white dishes which were prized in the Ottoman Empire, the greater Middle East and India, it seems that Temasek (14th century Singapore) was the most likely intended destination of the Temasek Wreck. This being the case, the recovered ceramics and artefacts provide an incredible insight into the utilitarian, elite, and ceremonial wares that were either used by the inhabitants or re-exported. And again, because the wide variety of Temasek Wreck ceramics was lost at a specific moment in the 14th century, they can be particularly helpful in interpreting Temasek era stratigraphy as revealed in past and future terrestrial excavations in Singapore.

For a detailed report on the Temasek Wreck, covering the discovery, survey, excavation, cleaning and conservation, wrecking process, artefact overview, Temasek parallels, dating, likely vessel type, likely port of lading, and likely destination, refer to The “Temasek Wreck (Mid-14th Century), Singapore: Preliminary Report”.6

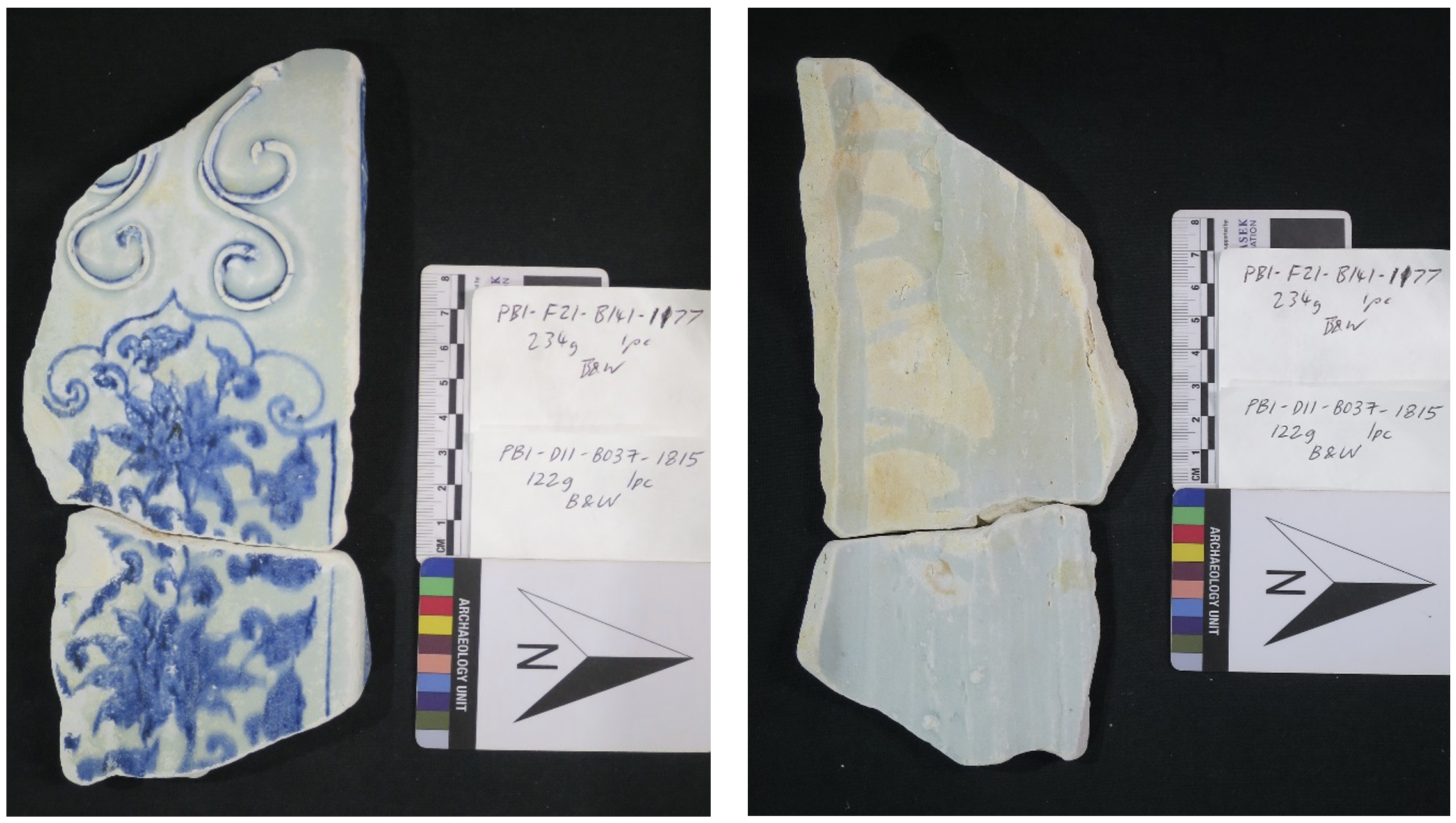

The Database

This Database deals with a specific element of the Temasek Wreck ceramics cargo, the Yuan dynasty blue-and-white porcelain. It documents every blue-and-white piece recovered from the wreck, from intact and nearly intact objects to tiny shards. Virtually every shard was coral encrusted, although the vivid hues of cobalt blue could generally be detected amongst the monochrome wares. Gentle citric acid and manual cleaning eventually revealed the full repertoire, including a number of red-and-white shards. These have been included in this Database as they were made in the same kilns over the same period using the same techniques. The copper pigment, however, was harder to master than the cobalt.

Once all of the blue-and-white porcelain from the Temasek Wreck was catalogued, detailed statistical analysis could be undertaken. Analysis comes in two forms: a distribution analysis which examines the spatial arrangement of the ceramics at the time of excavation; and a compositional analysis which determines the proportion of each ceramic shape and/or decoration in the cargo.

The blue-and-white porcelain Database is a subset of the Temasek Wreck Ceramics Database. Some of the database fields remain constant for blue-and-white porcelain while others do not. The fields are as follows:

Unique Identification Number (UIN) The UIN may be allocated to a single artefact or to a group of artefacts with the same Grid, Batch Number, and characteristics. Each UIN forms a Record in the Database. The UIN is sequential from lowest to highest. Gaps in the numbering occur where non-blue-and-white ceramics have been logged.

Grid The wreck site was divided into Grid squares measuring 5 x 5 metres, each with a unique alphanumeric designation. This locational information is fundamental for determining artefact distribution, which in turn reflects on the wrecking process.

Batch Number One or more Batch Numbers were allocated for each day on site. Each Batch Number corresponds to a Grid, a date, and a dive number (and hence the divers that excavated a particular artefact).

Glaze Type For this database the Glaze Type is always blue-and-white (B&W), apart from rare examples of red-and-white (R&W) porcelain, which are of the same style and were made in the same kiln complex, and are therefore included.

Kiln For the blue-and-white porcelain Database the Kiln is always Jingdezhen.

Material For this database the Material is always Porcelain.

Description Description here refers to the shape and/or type of object, i.e. bowl, cup, dish, jar (guan), jarlet, vase, etc.

Size The so-called size is not an overall descriptor but is only related to other objects of the same Description, i.e. bowls may be small, medium, large or very large but only with respect to each other.

Weight Weight refers to the combined weight of all artefacts in the one record.

Quantity Quantity is the number of artefacts occurring in the one record.

Condition Condition is 'shard' (or 'shards') for the vast majority of artefacts. Other terms reflect on the type of shard, i.e. 'base' for complete footring, 'base shard' for part of a footring, 'rim shard', etc. Some of the more complete pieces will have their degree of completeness recorded as a fraction.

Decoration External Decoration is typically the subject of the blue painting, ‘ducks in a lotus pond’ being the most prevalent. There may be several themes on one object, including ‘scrolls’ and ‘lotus panels’. External typically refers to the convex side of an object, i.e. the outside of a bowl, dish, jar, etc.

Decoration Internal As above but Internal typically refers to the concave side of an object, i.e. the inside of a bowl or dish. Closed shapes such as jars and vases do not have internal decorations.

Remarks Remarks covers anything out of the ordinary, that is not sufficiently covered by any of the other prescribed fields.

Images Every record has at least two images. All available images of each Record are provided in full resolution. The second image shows the less significant side of an object.

Highlight Highlight is either a ticked box, or a 'yes'. A tick or a 'yes' indicates that the particular record is rare and/or unusual, or of higher quality than normal.

Distribution Analysis

Artefact distribution analysis is a fundamental part of maritime archaeology. It is one of the primary tools used to determine cargo stowage configuration and the wrecking process. The other primary tool is the mapping of surviving hull remains. As there were no hull remains whatsoever on the Temasek Wreck site, artefact distribution analysis becomes the only tool.

Until all the ceramics have been catalogued and analysed, the blue-and-white porcelain must serve as a proxy. On a less disturbed wreck site, this would not be valid. Higher value cargo was usually better packed, more securely stowed, and positioned in the least vulnerable cargo space. It is therefore not representative of the cargo as a whole. As it turns out, the dynamic nature of the Temasek Wreck site has all but eliminated the influence of such variations. With nearly 700 years of strong currents acting in tandem with monsoon waves in shallow water, the ceramics cargo has been smashed to pieces and spread far, but not wide. Interestingly, the shards have scattered over 70 metres in a north-northeast / south-southwest orientation. And yet the width of this spread is only 20 metres at the widest point. To the south the lateral spread is only 15 metres, and to the north it is a mere 10 metres.

As deduced in the Preliminary Report, the wrecking scenario unfolds with first impact on shallow boulders to the east of the main wreck-site. The northeast monsoon wind and waves then drove the partially submerged hull westwards along a rocky promontory, until it shattered and sank in the vicinity of an adjacent sandy basin. The ship never ‘came to rest’. If she went down early in the northeast monsoon, which typically lasts from mid-November until mid-March, she may have been rent asunder within the one season. If later, she may have survived more or less integral for a year or so. But it is unlikely that a wooden hull would have survived intact through two monsoon cycles.

Ceramics stowed in boxes would not have moved far, until the boxes were smashed or rotted away. Barrels of ceramics could potentially roll along the seabed, between or even over low-lying boulders. Intact and nearly intact ceramics found well to the north-northeast imply that this did occur.

The current regime is discussed in detail in the Preliminary Report. In short, the bathymetry hinders tide induced currents flowing to the southwest, but intensifies those flowing to the northeast. During the northeast monsoon, strong wave-driven oscillatory motion would agitate the seabed. Spring tide currents in excess of 3 knots would then sweep mobilised shards to the north-northeast. On a relatively flat seabed the spread would have been fan-shaped. In the case of the Temasek site, the bathymetry contained the lateral spread. Shards were constrained to the sandy basin to the southwest, and then to a series of narrow gullies to the northeast. Their onward passage was only halted when the increasing water depth reduced seabed wave impact and current speed.

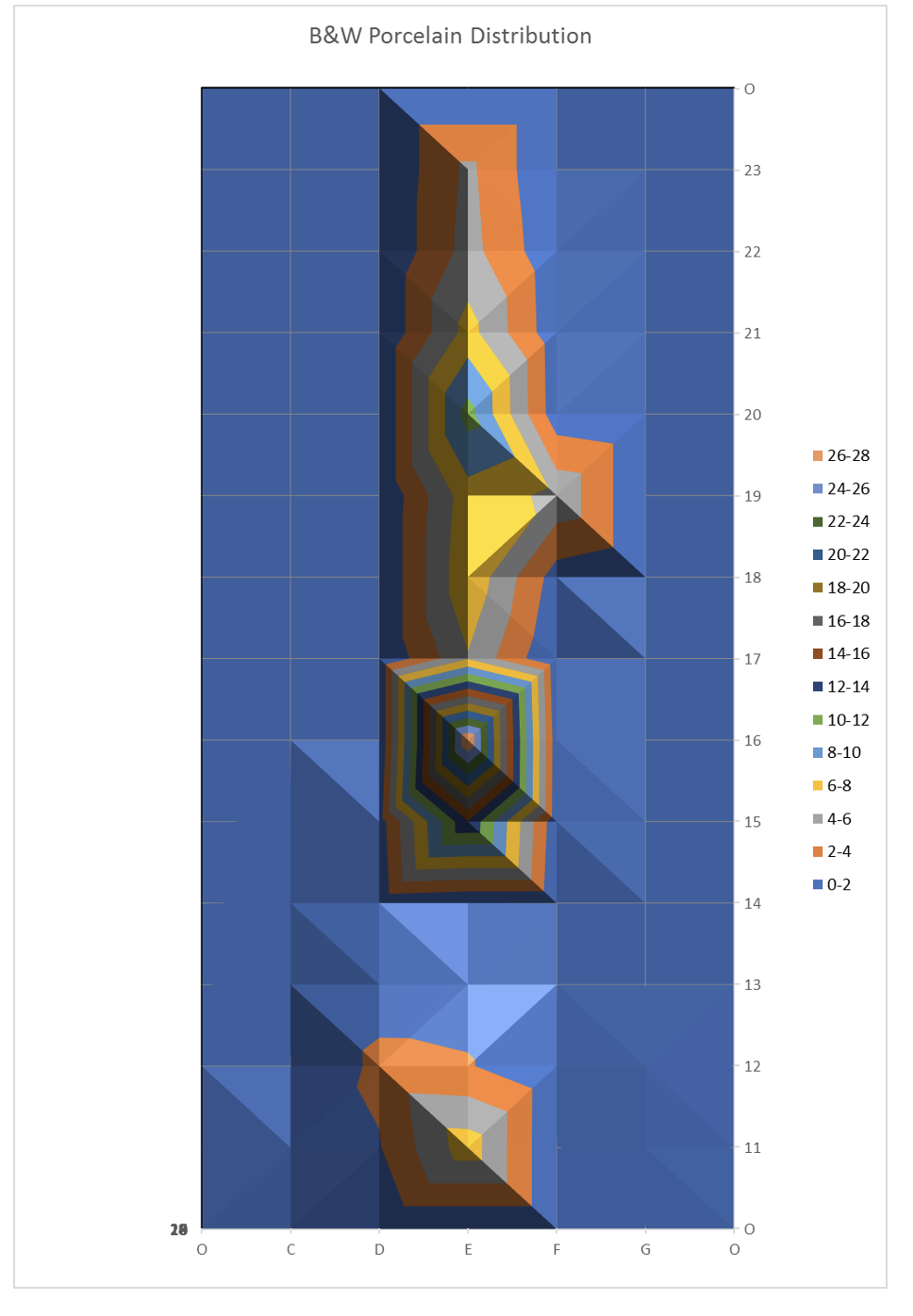

The distribution graph for blue-and-white porcelain shows a concentration in Grids D11, E11, D12 and E12, corresponding to the inshore sandy basin, which was referred to by the divers as the Graveyard. Very few shards were recovered from adjacent Grids D13, E13, D14 and E14, an area covered mostly by exposed bedrock. In marked contrast, the next three consecutive Grids, E15, E16 and E17, referred to as the Outer Graveyard, contained the highest ceramics concentrations. Proceeding further to the northeast the concentration remains higher than the inshore basin and only tapers off by Grid E23.

Clearly the pattern is not just the result of waves and current. The concentrations directly correlate to the depth and extent of sediment. The inshore basin is largely sand, but the layer is generally less than half a metre deep to bedrock. Offshore from the basin, the exposed bedrock provides no refuge for shards. But beyond that there are wide and deep sediment-filled holes, particularly in Grid E16. With over 30 kg of blue-and-white porcelain, this grid had more than double the next highest grid concentration, which occurred in the adjoining Grid E15. The deeper sediment continued to the northeast, but the gently sloping gulley bifurcated and narrowed, reducing the sediment volume.

The extremely dynamic nature of the site is well demonstrated in Grid E16, where the maximum depth of sediment was approximately 1.5 metres. Virtually every shard was coral encrusted, whether exposed on the surface or lying on the bed rock. Therefore, over the centuries, every shard has been fully exposed for long enough to be colonised by hard corals. Plastic debris was found at least a metre under the sediment. During severe weather events it seems the entire sediment layer can be displaced, even in the deepest pockets.

Perhaps even more striking is the scatter of shards from single notable objects. Large Yuan blue-and-white flasks, modelled on Middle-Eastern metal flasks, are extremely rare. Several shards from at least one such flask were recovered from the Temasek Wreck. Two of these shards have been pieced together to form one side of a single flask (see below). They were found in grids D11 and F21, implying a minimum scatter of 45 metres. Three matching shards form another side of a flask, probably the same one. They were found in grids E16, E17 and E23, implying a minimum scatter of 30 metres. Two matching shards from a rare lobed vase were found in grids E16 and E22, a minimum of 25 metres apart.

It may therefore be concluded that ceramic distribution has been overwhelmingly driven by environmental conditions and bathymetry. The spatial disposition of ceramics can tell us relatively little about the initial wrecking process, and it can no longer tell us anything of stowage patterns.

As a secondary analysis of the wrecking process, the blue-and-white distribution has also been plotted by shard weight. On a mildly dynamic wreck site, the heaviest shards would be expected to remain in the vicinity of the sinking position, while the lightest shards would be carried the furthest by current and wave action. As it turns out the distribution by weight is nearly identical to the total distribution. The heavier shards have been as widely disbursed as the lighter shards. Therefore, the sinking location cannot be deduced by this means either.

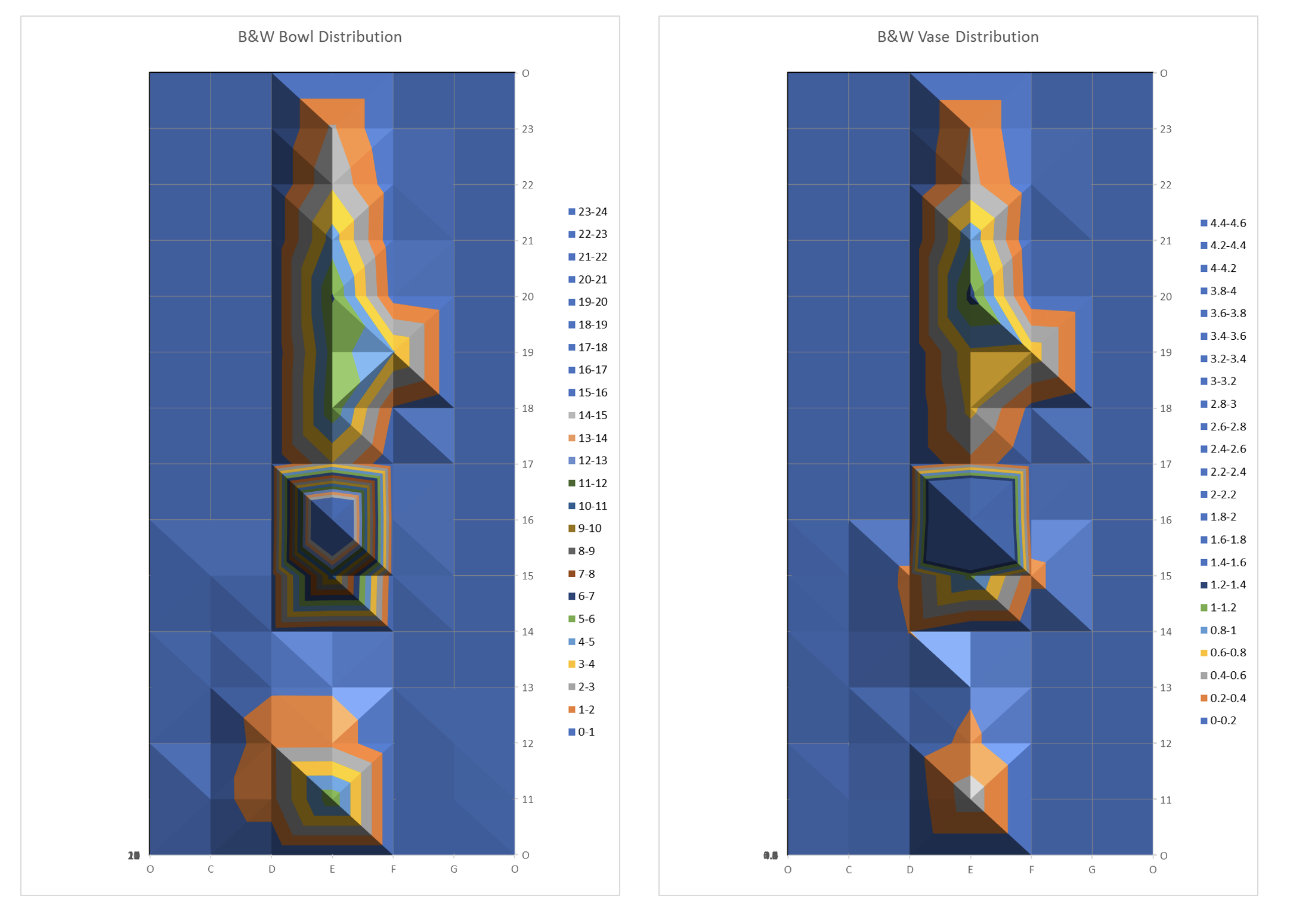

One further check on stowage patterns can be made by investigating the distribution of different ceramic shapes and decorations. The distribution of bowls, the most common shape, mirrors the total distribution, so it would seem that the dynamics of the site once again obscure the original stowage configuration. Likewise, the distribution of vases. They are not as widespread as the far more common bowls, but peak concentrations all occur in the same Grids. Taking the analysis one step further, when comparing the distribution of bowls decorated with ‘ducks in a lotus pond’ with bowls decorated with ‘lotus bouquets’, there is yet again no discernible difference.

Compositional Analysis

Fourteen different shapes have been recorded. By far the majority are bowls, making up 71.3% of the total by weight. Next are vases at 11.3%, and guan (jars) at 9.6%. Note that as this analysis is by weight, the original number of heavy guan would have been far less than the original number of lighter vases. Dishes are next with 3.6%. Flasks and stem bowls make up 1.1% and 1% respectively. All other shapes combined account for only 2.1% of the total.

Looking specifically at the two most popular decorations on bowls, there are three times more ‘ducks in a lotus pond’ than ‘lotus bouquets’. When considering only bases or base shards, where these decorations occur, 56% of all bowls are decorated with ‘ducks in a lotus pond’ while 17% have ‘lotus bouquets’.

The most robust element of a bowl is the base, where the footring provides reinforcement. The total number of intact or nearly intact bases provides the minimum number of bowls in the original cargo. Consequently, we know that there were over 300 blue-and-white bowls of varying size onboard the Temasek Wreck.

In stark contrast there were only nine intact or nearly intact vase bases. However, the total number of vase shards suggests at least double that number of vases, based on an average weight of 700 g per vase. Unfortunately, the total weight of shards is not fully representative as many shards were too small to recover.

The total weight of cover, cup, ewer, jarlet, and stem cup shards suggests that there were only a handful of each of these shapes in the cargo. There may have only been one or two bottles, ewers, pots and pouring bowls. Note, however, that ewers could only be categorised when spouts or handles were encountered. Some of the so-called vase shards may have been from similarly shaped ewers.

The total weight of red-and-white shards is a mere 299 grams, or 0.2% of the total. They are all from vases.

| Type | Weight (gms) | Qty of shards | Average weight/shard (g) | % of total weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottle | 768 | 5 | 154 | 0.6% |

| Bowl | 96,696 | 1,378 | 70 | 71.3% |

| Cover | 338 | 21 | 16 | 0.2% |

| Cup | 271 | 18 | 15 | 0.2% |

| Dish | 4,843 | 50 | 97 | 3.6% |

| Ewer | 533 | 27 | 20 | 0.4% |

| Flask | 1,448 | 9 | 161 | 1.1% |

| Jar/Guan | 13,023 | 78 | 167 | 9.6% |

| Jarlet | 453 | 20 | 23 | 0.3% |

| Pouring bowl | 65 | 2 | 33 | 0.1% |

| Stem bowl | 1,292 | 6 | 215 | 1.0% |

| Stem cup | 358 | 8 | 45 | 0.3% |

| Unknown | 134 | 4 | 34 | 0.1% |

| Vase | 15,348 | 727 | 21 | 11.2% |

| Total | 135,663 | 2,356 | 100.0% |

Conclusions

The distribution analysis demonstrates that the long-term wrecking process was driven by bathymetry and environmental conditions. The distribution has been so dynamic that it is no longer possible to make a confident assessment of the wrecking process immediately after impact, and it is impossible to make any assessment of original cargo stowage patterns.

The compositional analysis is useful for determining relative quantities of different ceramic shapes and decorations. A count of bases is perhaps more appropriate for determining minimum quantities of bowls, which stands at over 300.

By uploading the blue-and-white porcelain Database it is now possible for researchers to carry out their own single or multi-level analyses. Potential permutations are only limited by the imagination.

Every shard has been photographed from at least two angles. With these images included in the Database, more detailed descriptions are possible for those so inclined. This allows for even higher levels of statistical analysis or greater insights into shapes and decorations that are perhaps unique to the blue-and-white porcelain cargo from the Temasek Wreck.

Acknowledgements

The excavation phase of the Temasek Wreck project was generously and robustly supported by various Singapore Government Ministries, Institutions and individuals, all of which have been acknowledged in the Preliminary Report. The post-excavation documentation of the ceramics cargo, again, is fully supported by the National Heritage Board (NHB), through the efforts of Senior Director, Mr Yeo Kirk Siang, Director of Heritage Policy & Research, Ms Melissa Tan and Senior Manager, Ms Cai Ying Hong. In many respects, the ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute (ISEAS) has been carrying out the work on behalf of the NHB, through Deputy Director, Dr Terence Chong and Senior Research Officer, Ms Fong Sok Eng.

Dr Tai Yew Seng, as an ISEAS Visiting Fellow, initiated the documentation of the Temasek Wreck ceramics cargo. As a one-man-show, with over 3.5 tonnes of shards to process, Record sizes were necessarily larger than optimal. When the author accepted the reins a few months into the process, Karen Tan stepped up as our first volunteer. She is responsible for resorting and documenting much of the blue-and-white porcelain that features in the database. Patricia Bjaaland Welch, Secretary of the Southeast Asian Ceramic Society, came to the rescue with more volunteers from the Society and from the Asian Civilisations Museum Friends of the Museum. These knowledgeable and enthusiastic ladies have proved a godsend, washing, sorting, weighing and photographing a seemingly endless flow of shards. Through their efforts, the entire Temasek Wreck ceramic cargo is now ready for online publication, not just the spectacular blue-and-white.

- Anon., 2011, ‘Survey Report of the Shiyu Wreck Site in the Paracel Islands’, Journal of the National Museum of China, pp. 26–46.↩

- Carswell, J., 2000, Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain Around the World, London: British Museum Press, pp.160-171.↩

- Gardellin, R., 2023, ‘Chinese Trade in the Red Sea’, in Orientations, May/June, pp. 58-64.↩

- Gotauco, L., R.C. Tan & A.I. Diem, 1997 Chinese and Vietnamese Blue and White Wares Found in the Philippines, Makati City: Bookmark, p.36.↩

- Barnes, L.E., 2010, Yuan Dynasty Ceramics, in Zhiyan Li, Bower, V., Li He (Eds), Chinese Ceramics: From the Palaeolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty, Yale University Press: pp331-386, p.375.↩

- https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Flecker_TWPS04_Final_r.pdf↩