Innovation and China’s Global Emergence

edited by Erik Baark, Bert Hofman, and Jiwei Qian

ISBN: 978-981-325-148-9

published August 2021

Or read this open access web edition

Chapter 9

Made in China 2025 and the Proliferation of Intangible Assets

Anton Malkin

Introduction

In 2015, Made in China 2025 (MIC 2025) was released to much criticism. Critics claimed that this plan was a thinly veiled import substitution programme that sought to push foreign technology firms and manufacturers out of the Chinese market. The Chinese government defended it as consistent with the long-term policy objective of Reform and Opening Up, emphasising China’s need to overcome the middle-income trap. The Government also pointed out that MIC 2025 called for strengthening of intellectual property (IP) law and further FDI liberalisation.

This chapter asks: How can we reconcile these dramatically opposing views? The data and analysis presented here suggest that, paradoxically, the conflicting narratives carry grains of truth, but obscure the challenges facing China’s industrial economy in the near and medium term and the ways in which MIC 2025 seeks to overcome these challenges. It argues that the evolving logic of globalisation, long-standing problems of technological catch-up and economic development, reinforced by the growing importance of the intangible economy—defined by the commercialisation of, and business strategies centred around, intellectual property (IP) like patents, trademarks, copyright and data—create real tensions in China’s path to catching up with advanced manufacturing economies like Japan, Germany and Korea. It briefly examines China’s progress in technological standardisation and its growing portfolio of intellectual property assets and shows that despite the intrinsic contradiction in MIC 2025’s insistence on both self-sufficiency and globalisation, China’s continued integration into the global intangible economy creates potential tensions between China and other advanced economies.

This chapter explains that the MIC 2025 plan is inseparable from China’s expanding intangible economy and is one piece of a multi-pronged strategy to move China up the global value chain hierarchy. It should be viewed alongside China’s automation, standardisation and IP commercialisation strategies. These components of China’s economic evolution conform to changes in patterns of globalisation, which are increasingly defined not only by the global division of labour in supply chains—a key aspect of post-Cold War trade and finance-driven globalisation—but also by the proprietorship over intangible assets like patents, data, standards and brands. In this respect, MIC 2025 tells us as much about significant changes in the global economy, as much as it tells us about the forward trend of China’s industrial policy planning. This chapter explores MIC 2025 in the context of the intangible economy and explains how China’s plan to transform its manufacturing sector plays out in its drive to standardise manufacturing, commercialise IP and influence Chinese firms’ mergers and acquisitions (M&A) decisions and IP asset acquisitions more broadly.

An Industrial Policy for the Intangible Economy

In principle, MIC 2025 is about moving Chinese electronics manufacturers, many of which are private, up the chain of value creation. Indeed, the acceleration of the move from low-end manufacturing prompted by the trade war with the US is not an impediment to China—indeed, it reinforces MIC 2025. The plan sees China effectively abandon its role as the workshop of the world, and join the ranks of Germany, Japan and South Korea in specialising in automated, “intelligent”, highly productive manufacturing activities. It also sees Chinese firms join the ranks of US multinational corporations (MNCs) in controlling the patents, brands and data that allow top global firms to generate revenues from global production without having to directly engage in physical manufacturing. In a sense, China wants to have its cake and eat it too: to create and own the technologies that go into advanced manufacturing facilities, and to engage in the physical manufacturing processes that put these technologies to work.

To be sure, many aspects of the plan are familiar to students of East Asian industrial policy. Despite the novel focus on intangible assets, MIC 2025, at its core, seeks to align government priorities with the commercial interests of its manufacturing firms, providing government funding (typically through venture capital, tax rebates and industrial park construction; see Malkin 2018). But unlike South Korea, Japan and other smaller developmental economies, MIC 2025 does not focus on export-driven rapid catch-up development. Instead, MIC 2025 is focused on the domestic economy. Critics typically assert that MIC 2025 is about displacing foreign firms globally. However, the document—with its ambitious targets of domestic supply (see Wübbeke et al. 2016)—focusses on the domestic market, projecting the global competitiveness of Chinese manufacturing brands far into the future (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1: Timeline for Achieving MIC 2025 Goals

Step 1 | |

• By 2020, consolidate manufacturing | |

• By 2025, Information Technology will be comprehensively integrated into manufacturing (Industrial Revolution 4.0) and China will have well-known global MNCs specialising in manufacturing | |

Step 2 | |

• By 2035, Chinese manufacturing will reach an “intermediate” level (behind Germany, Korea and Japan, but substantially ahead of middle-income economies) | |

• China will lead global innovation in sectors where China is most competitive (i.e. MIC 2025 sectors) | |

Step 3 | • By 2049, China will become the leader among global manufacturing powers |

What, then, is MIC 2025 all about? Consider the diagnosis offered in the document of what is wrong with China’s manufacturing industry. It highlights the fact that manufacturing in China is facing [a] “two-way squeeze” (双向挤压): from developed countries at the top and developing countries at the bottom. It notes that China has few world-renowned brands and that its “independent innovation capability” is weak; it also highlights that its industrial structure and service sectors are “immature”. It urges the country to move from “made in China” to “created in China” (实现中国制造向中国创造的转变), putting an emphasis on R&D and brand development. Indeed, the document reads more like an innovation strategy rather than an import substitution programme.

As explained below, this framing is the result of the underlying logic of MIC 2025—the growing importance of the intangible economy in manufacturing. The intangible economy is defined as the commercialisation of, and business strategies centred around, intellectual property (IP) such as patents, trademarks, copyright, data, as well as research and proprietary knowledge. The intangible economy creates pressures not only for global economic integration—as intellectual property laws and norms in major markets increasingly converge towards more private ownership of IP assets—but by a degree of self-sufficiency as well.

As Haskel and Westlake (2018) argue, intangible assets are different from tangible, fixed asset investment in part because they are more difficult to value through traditional accounting methods, are more scalable (because they are not physical and do not have physical production constraints) and generate productivity and economic value in less predictable ways. One could also add to this collection of distinctions the problem of industry concentration. Because intangible assets are associated not with the ownership of financial or physical capital, but fundamentally concern the ownership of ideas, it is easier to exclude competitors from collecting the rents and value generated by these ideas (for example, through the legal system) than to price out competitors or create better products. Simply put, there is no such thing as a totally new idea, and increasingly, owners of “new” ideas (like owners of patents of a new technology) cannot make a new product without paying licensing fees to owners of ideas on which new inventions are built. As such, barriers to entry in industries like semiconductors and telecommunications are higher than ever before and make economic development through the import of technology and physical capital less effective than in the past. This paradox of openness begetting zero-sum gains stems from the growing importance of the rents and revenues accruing to firms and countries from owning a greater share of intangible assets that, while traded globally, are created and deployed locally.

Emerging Industries Made in China: AI, Automation and

the Intangible Economy

In 2019, in response to Made in China 2025 being featured heavily in the United States Trade Representative (USTR) 301 investigation, the Chinese authorities began to downplay the role of the plan in China’s national development strategy. Needless to say, policy action and policy messaging are not one in the same. While MIC 2025 may decline in name, the sectoral catch-up goals are unlikely to be dropped from China’s economic development strategy going forward.

This is because MIC 2025 is as much a descriptive outline of China’s technological development strategy as it is a call to action. First, while MIC 2025 is about manufacturing at its core, observers have largely misunderstood the role of manufacturing in China’s plan to climb global value chains. Simply put, manufacturing sectors’ prowess should be understood as a means to an end, rather than an end itself. This is because grabbing a higher share of output in the global economy of the twenty-first century is not about making things, but about owning the brands, patents, copyrights and data that arrange how things are made, where they are made, and who collects the revenues when goods move across borders. This, in a nutshell, is the definition of the intangible economy in the context of manufacturing.

MIC 2025, in its original State Council pronouncement, was explicit about how China’s manufacturing sector is seen as evolving. Automation, intelligent manufacturing (the “industrial internet of things”) and standardisation are seen as the means to achieve China’s value chain ascent. But the goal of manufacturing component self-sufficiency is, rather, a national security-based imperative to achieving the goal of intangible economy competitiveness.

As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted in their 2019 Article IV consultation on China, “China has a more advanced industrial structure than its income level would suggest. The share of high-tech in industrial value-added was 43 per cent in 2015 […], similar to the level in Belgium and Spain, where income levels are about three times higher” (IMF 2019: 13). This suggests that MIC 2025 is less trendsetting and more trend-following in its aspirations. Simply put, China has already moved a long way towards manufacturing sophistication, but its firms continue to lag in capturing the value created from this advanced structure.

In this respect, MIC 2025’s sectoral self-sufficiency approach uses the wrong metrics to assess the plan’s success or failure. Therefore, the stated goals of sectoral supply self-sufficiency are inappropriate measures if the goal is to see its manufacturing industry occupy a high position in global value chains (GVC). Supplying components only is a very inadequate goal, as component supply occupies the mid-range in the GVCs. As Xing explains in this volume (p. 265), “A lead firm, which manages the operation of a value chain and decides the relations between firms participating in the chain, is necessary for any meaningful GVCs”.

Why is it important to have leading firms with global reach occupying the top of GVCs in their respective (or multiple) sectors? The answer has less to do with protectionism, in the classical sense of the term, and more to do with the nature of the intangible economy. It has less to do with which firms have access to China’s market, or how much China exports, and more with to do with how much value Chinese firms capture from both existing and emerging technologies. In the global intangible economy, self-sufficiency in component manufacturing does not mean physically producing “core components”, but rather possessing the right to produce these components at the exclusion of others, the ability and expertise to produce these components and the ability to earn revenues from the products they produce.

How, then, should we begin to assess China’s industrial policy goals in the intangible economy? How should we interpret the tensions they create between China and other advanced economies? I propose looking specifically at the standardisation efforts and IP asset growth in China, and suggest that tracking China’s IP balance of payments—the difference between payments and receipts for IP—offers a glimpse of the progress of China’s intangible economy more broadly as well as its relationship with other players in the global intangible economy.[1] I suggest that while there is already a flourishing market for intangible assets in China, Chinese firms, universities, and research institutes are still substantially behind their foreign rivals in commercializing their own technology portfolios.

Standards as a Pathway to Globally Competitive Manufacturing

Standards are an important means for countries to overcome being stuck in lower tiers of GVCs. MIC 2025 offers a conflicting narrative of China’s industrial upgrading strategy. While discussing the need to promote Chinese firms’ standard-setting capabilities, the plan nevertheless promotes both quantitative targets for sectoral self-sufficiency in “core component” supplies and moving away from physical goods production towards intangible production.

Global value chains—broadly defined as the division of labour among firms and countries along the chain of stages of production, from basic assembly on one end through product development to branding on the other—are inherently hierarchical, with standard-setting and IP-owning firms at the top, setting prices and creating product specifications. These specifications may be open-source or proprietary, but in all cases technological standards set parameters for components manufacturers and final product assemblers that perform specialised manufacturing tasks. Standard-setting firms embed themselves in GVCs by establishing arms-length relationships with suppliers, but also by ensuring quality consistency, reliability of component and assembly manufacturing supply chains, and creating managerial consistency along these supply chains (von Hagen and Alvarez 2011). Standards are generally set behind closed doors by industry associations, governments and intergovernmental organisations.

The hierarchy in GVCs could partly be understood as a distinction between standard-makers and standard-takers. While some standard-makers like Intel, TSMC and Samsung both set standards and own manufacturing operations directly and through sub-contracting, other firms, such as Qualcomm and Intellectual Ventures focus exclusively on R&D and product standardisation. These firms often file for IPR protection for their R&D output under the category of standard-essential patents (SEP), meaning that their component design is standard-essential in that it comprises a product that is not only essential in a particular supply chain, but is also proprietary (more on this below).

The hierarchy in GVCs is defined both by productivity and by the ability to adjust to new product development and other disruptions in the existing chain of supplying global goods. Adjustment for contractors downstream in the supply chain value spectrum (for instance, factories that specialise in final assembly of various products) is typically a challenge. Small contractors involved in standardised assembly of commodified goods like fabrics, plastics and glass often have low leverage in the production cycles and final demand for their products because they are separated from the final product by multiple layers of players in the supply chain. For instance, coastal contract manufacturers in China must negotiate not only with component suppliers in Korea and Japan, which make the components that the former put together, but also with buyers in destination markets—namely, retailers, brand owners and importing firms.

By contrast, owners of global brands and firms with large quantities of standard-essential patents (SEPs) are able to command the structure of global supply chains due to their proprietorship of the intellectual property that encompasses the final goods that consumers and large organisations purchase (Schwartz 2019). Small and large manufacturing contractors, as well as manufacturers of components that feed into final assembly, must abide by the intellectual property laws and norms set in core markets if they are to maintain their supplier-buyer relationships across the global economy. Murphree and Anderson (2018: 123–36) suggest that constraints placed on firms can be explained not only by global value chain theory, but also by resource dependence theory (RDT) (see Hillman, Withers and Collins 2009: 1404–27), which was developed in international business and management literature to explain the strategic constraints placed on firms reliant on government contracts and the costs of switching business models that such constraints entail. In their study of Chinese manufacturing contractors, Murphree and Anderson showed how this concept can be applied to firms downstream from IP-owning at the top of the global value chain hierarchy. They are constrained by choices made by leading global IP owners, with adjustment burdens of novel manufacturing techniques and markets falling on the smallest players, particularly sub-contractors in China’s manufacturing regions.

RDT can also be applied to standards-abiding firms at the bottom of this hierarchy. To explain how, we need to understand how standards are set and the power they confirm on standard-setting firms. Standards are set with a variety of purposes: phytosanitary precautions (for example, food safety), conformity to domestic markets (for example, different electric outlet design and driver seat placement in automobiles) and electronic component compatibility (for example, cellular phone charging cables). In manufacturing, standards define specification on everything from the design of a factory floor, to the size and weight specifications of manufactured goods. GVCs cannot function without standards. Indeed, the very process of modern globalisation could be said to be underpinned by something as simple and ubiquitous as shipping container standards, which define not only the processes and inspections that make the transit of global goods possible, but also define the size and quality of global manufactured goods (Girard 2019).

In terms of RDT, resources can be defined as the dependence of manufacturers on the specifications of the types of goods they can produce and how such goods are to be produced. Small sub-contracting manufacturers have little input over the direction of GVC structure, as technological standards are set by committees of engineers and government representatives at both the national and international levels. Moreover, the capacity to influence and create global standards does not simply benefit standard-setting firms, but also influences the capacity of the country where such firms are domiciled to adapt to the changing structures of globalisation—and to exert relative gains from said structures. As Girard (2019: 5) describes it, standards are more than just publicly available instructions for producers and retailers:

Once developed, they become copyrighted documents. Standards get published and sold to users. Buyers include all players in supply chains from the producers of raw materials, those who provide parts, components and systems to the manufacturers of assembled goods, product testing laboratories and conformity assessment bodies.

In short, setting standards is profitable and reduces dependence on exogenous inputs under RDT. By contrast, MIC 2025 posits an endogenous model of component self-sufficiency. Standard-setting, by contrast, creates opportunities for Chinese firms to take proprietorship over IP assets without the necessity to own and manufacture physical products, and to have a direct stake in the functioning of a global system that increasingly depends on the protection and commercialisation of intangible assets.

Following the controversy surrounding MIC 2025, policymakers seem to have internalised these lessons and expanded on the role of standards in China’s economy in a policy plan titled China Standards 2035 (中国标准2035). The promulgation of the government’s policy guidance towards the role of standardisation in China’s economy builds on an earlier State Council document, the 12 November 2013 Decision on Major Issues Concerning the Comprehensively Deepening of Reform of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee. This document stressed standardisation as part of the 18th CPC Central Committee’s stated goals of deepening the market allocation of resources and “comprehensively deepening reform” (Hui and Cargill 2017).

This adjacent plan lays out the government’s plans to promote the global promulgation of indigenous Chinese standards and their role in China’s economic development. There are important, large differences between China’s methods to promote standardisation and those of the US, Europe and elsewhere. In the case of the latter, standardisation relies largely on non-governmental professional associations and private firms to create national and international fora that discuss, assess, and set standards that all major global firms must rely on if they are to plug into integrated global supply chains and into global trade more broadly. These are not entirely different from financial standards that have a distinctly voluntary character (countries can receive a high rating in global financial markets if they comply) and food safety standards (which work based on market access denial for non-complying firms and jurisdictions). But, in a sense, they are more binding, due to the global reach of manufacturing supply chains.

In the Chinese case, however, technological standards see much more involvement on the part of the state. Although the role of the state in standardisation has been much critiqued and amended within China (Hui and Cargill 2017), regional governments and the central government still play an important role in the implementation of said standards. Today, it is not government bodies that propose and debate standards, per se, though government actors do set up institutions that bring together firms and professional associations (relying extensively on standardisation pilot projects) to promote indigenously developed standards and help promote them as well. As a recent work report on standardisation stipulates, the Chinese authorities have sought to bring China’s standardisation practices in line with those stipulated by the International Standards Organization and other international bodies (Li 2018). By contrast, in the case of mobile telecommunications, firms like Huawei and ZTE liaise directly with global associations like the Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) to promote technological standards based on in-house R&D at the global level.

These developments did not come out of nowhere. Indeed, the original MIC 2025 document laid out China’s standardisation goals and logic in detail and tailored these to explain how and why the manufacturing sector is undergoing changes, and the directions of the changes that Chinese authorities wish to emphasise and promote. As MIC 2025 states, China’s manufacturing sector should do the following:

Give play to the important role of enterprises in the formulation of standards, support the formation of standards-oriented industry alliances, build standards innovation research bases, and jointly promote product development and standards development. Develop enterprise group standards that meet market and innovation needs and establish self-declaration disclosure and supervision systems for corporate product and service standards. Encourage and support enterprises, research institutes, and industry organisations to participate in the formulation of international standards and accelerate the process of internationalisation of China’s standards [emphasis added] (State Council 2015; author’s translation).

Why has the central government decided to take a leading role in the promotion of China’s strength in international standard-setting? In part, this speaks to the significance of the role of standards in ensuring the ascent of Chinese firms in global value chains. The analysis here highlights the importance of tracking Chinese firms’ progress on the setting of standards and the globalisation of China’s standards. But tracking standard-setting offers only a partial picture of the progress in China’s intangible economy and its role in GVCs. This chapter proposes that there is an additional way of looking at China’s progress in this regard, namely, quantitative measures of China’s IP balance of payments. The rest of this section offers examples of data and brief analysis that speaks to the importance of examining IP payments as an approach to understanding how Chinese firms are progressing towards the goals of MIC 2025.

Balance of Payments in IP

The role of IP in a country’s balance of payments has been documented (Neubig and Wunsch-Vincent 2017) but remains under the radar in the analysis of China’s macroeconomic surpluses with the rest of the world. As China’s surplus has been shrinking in recent years (Wei 2018) and trends towards either deficit or balance in the medium-term (Malkin 2018), it is important to understand the role of IP payments in this broader story. As China’s economy becomes increasingly intangible-asset oriented, the pressure of the economy paying to the rest of the world more than it receives is exacerbated, in particular by the growing role of IP licensing payments.

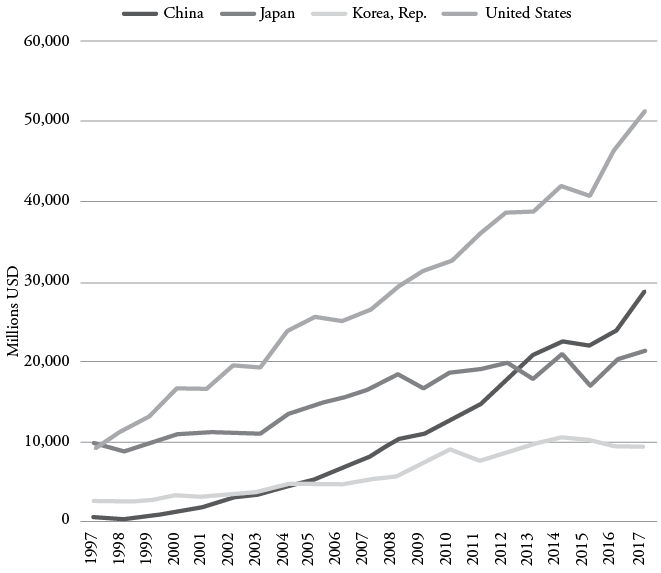

To understand this further we need to look not only at high-tech industrial value added but at intangible asset ownership. As Figure 9.1 shows, China has become a major source of IP rents for MNCs since WTO accession. This is a product of growing IP protection and the growing importance of China as a market for global technology firms. This is due to the growing role of licensing arrangements between foreign firms and their Chinese counterparts. As Breznitz and Murphree (2013) have outlined, a significant but little-understood revolution in China’s technological development strategy has been taking place, pertaining to standards and patents. Throughout the mid-late 1990s and mid 2000s, Chinese firms treated IP like a cost of doing business—something to be minimised, rather than an essential strategic asset. This all began to change following China’s experience with its (by many popular accounts, unsuccessful) promotion of various domestically oriented telecommunications standards: namely, TD-SCDMA (Mobile), WAPI (Wireless LAN encryption), and AVD and CBHD (Digital disc players). While these standards had not exceeded their stature as lacklustre efforts to create a Chinese standard for China only (foreign standard-bearing components were still preferred by Chinese electronics and telecom vendors), the experience changed policymakers’ and firms’ understanding of IP development and commercialisation.

These efforts, along with China’s growing sophistication in technological innovation more generally (see WIPO 2019), have contributed to a shifting of the extant equilibrium of the Chinese IP market. Chinese firms have gradually come to see IP as a strategic asset rather than a cost of doing business. As Breznitz and Murphree (2013: 2) put it, “In commoditised industries such as consumer electronics, licensing fees squeeze already thin profit margins. Development of low cost and potentially competitive standards for similar or identical technology niches pushes foreign standards alliances to lower royalty rates. This has been a great boon to Chinese companies”. Made in China 2025 recognises these factors and envisions Chinese firms taking a greater slice of global standardisation efforts globally, as noted above, not only to promote scientific efforts and IP commercialisation, but to help its firms’ need to reverse the long-standing trend of being on the wrong side of a global intangible economy that is characterised in part by a division into IP-have and IP-have-not states.

Figure 9.1: Charges for the Use of Intellectual Property, Payments

(BoP, current US$)

Source: World Bank.

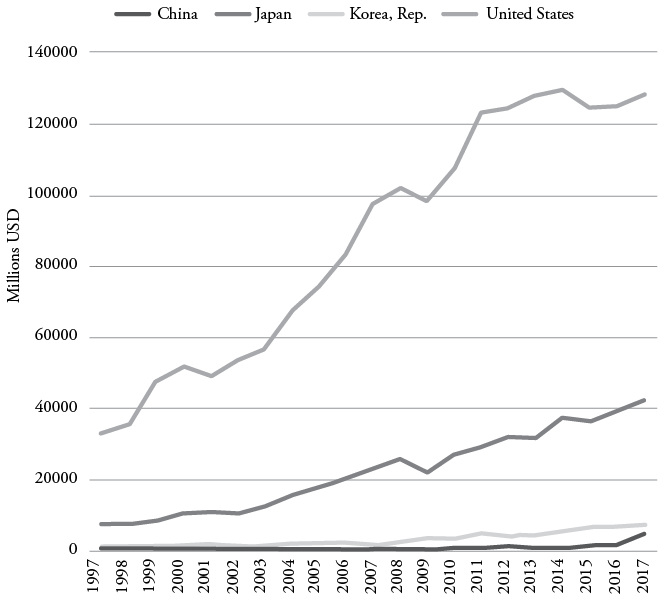

As Figure 9.2 shows, there remains a large discrepancy between how much Chinese firms pay for IP and how much they receive for it. The data is clear: while China’s IP commercialisation and protection have accelerated rapidly over the past two decades (and particularly over the past five years), China remains an IP have-not country. In the 21st century global economy, China cannot ascend global value chains without asserting the IP rights of its companies.

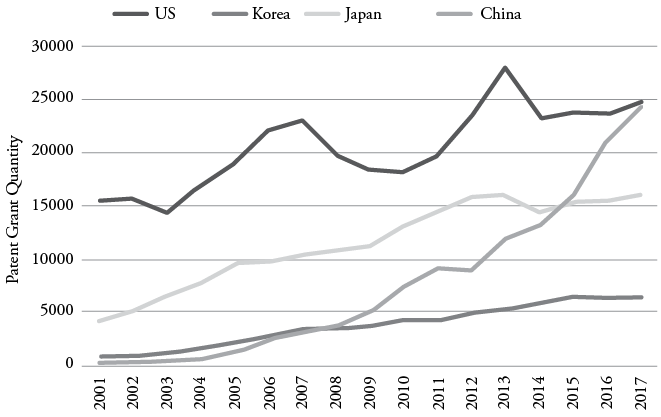

But can Chinese firms be considered owners of significant quantities of revenue-generating IP assets? This question remains contested in the literature on China’s innovation and IP development (Kennedy 2017; Malkin 2018; Yu 2018). However, from the perspective of collecting rents on patented assets, the potential for Chinese firms to earn revenues from their IP is also growing rapidly, as seen most vividly in China’s recent foray into technological standardisation (Murphree and Breznitz 2018: 1–55) and the growing appetite on the part of Chinese firms to register their patents as “standard-essential”—giving them the title of standard-essential patents (SEPs) (Ernst 2017), thereby giving them rights to negotiate technology licensing arrangements with global firms that utilise technology that includes the standards they had helped set in the first place. Why is this significant? As Figure 9.3 shows, the patent grants under MIC 2025 categories have been rising, exceeding those of Japanese and Korean firms and matching (in 2017) those of the US. While it remains to be seen how many of these patents are standard essential, it is worth noting that preliminary data in the field of telecommunications technology indicates that Chinese firms (notably Huawei, and to a lesser extent ZTE) boast a significant share of SEPs in new generation mobile communications—5G (IPLytics 2019).

Figure 9.2: Charges for the Use of Intellectual Property, Receipts

(BoP, current US$)

Source: World Bank.

To be sure, an IP payments deficit is not necessarily a bad thing. For instance, it highlights the growth of China as a viable market for IPRs for foreign and Chinese firms alike. Moreover, barring a detailed analysis of the specific IP assets underlying this deficit (a task beyond the scope of this chapter), it is safe to assume that many of the assets responsible for China’s outgoing IP payments comprise purchases of foreign technology and consumer purchases of foreign owner brands. In principle, if the US and its allies are comfortable with American, European and Japanese technology being utilised for technological innovation in China, and if China is comfortable with this interdependent relationship as well, there is no fundamental issue with China’s IP deficit.

Figure 9.3: Patent Grants under MIC 2025 Technology Categories

Source: WIPO.

However, much like a current account deficit, this deficit creates winners and losers. Chinese technology proprietors like Xiaomi and Huawei have spent years in Chinese and foreign courts seeking to renegotiate licensing payments demanded by foreign firms for SEP-protected technology that Chinese firms use in their finished products (Malkin 2020). This could go a long way in explaining why Chinese policymakers wish to see more manufacturing core component self-sufficiency. In simple terms, having Chinese manufacturers reduce their dependence on foreign technology would preclude the need for continued payments to foreign technology proprietors. This strategy, however, will not necessarily lower costs for Chinese manufacturers, especially if foreign-owned technology is more efficient than its Chinese counterparts and therefore earns more revenue in both domestic and global markets for Chinese firms.

Therefore, it is worth looking not only at how public policy promotes the goals of MIC 2025, but also at how Chinese firms—both state-owned and private—have been progressing towards the goals outlined in MIC 2025. As Figure 3 shows, Chinese firms have been vigorously patenting technological assets that could broadly fall under the categories outlined in MIC 2025, and they have been doing so since before the release of the plan.

The Messy Logic of Self-Sufficiency and the Role of Foreign Firms in MIC 2025

As explained above, MIC 2025 envisions China as an IP-rich manufacturing powerhouse. Where does this leave foreign, multinational firms? In other words, can the dual goals of industrial self-sufficiency and globalisation of Chinese firms be reconciled?

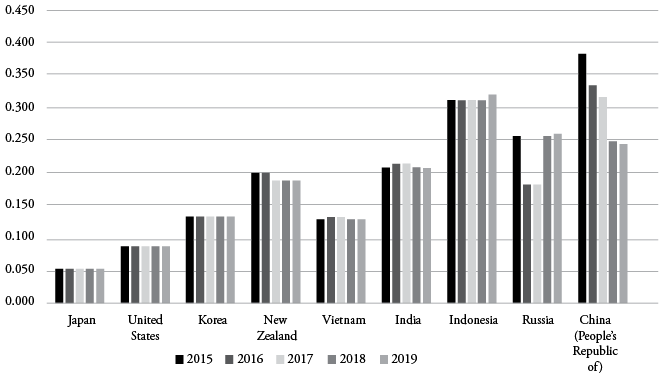

China’s FDI regime, according to OECD standards, is among the most restricted in the world among major economies, as Figure 9.4 illustrates, and gives Chinese firms a homefield advantage in demanding technology in exchange for market access.[2] The concern stems from several factors that have historically defined China’s Reform and Opening period which began in earnest in the early 1980s, but which have changed considerably over time. They include an SOE-dominated economy, where access to markets depends on contracts with these market players; a lack of intellectual property protection; a government eager to be involved in joint venture negotiations that involve important technology assets; and an active industrial policy framework involving SOEs, private firms, local governments and other actors, that aim to accelerate the process of China’s technological catch-up.

However, as a McKinsey (2019) report notes, China maintains a relatively high degree of foreign MNC penetration across a range of economic sectors—much more so, in fact, than the US. However, many commentators have argued that MIC 2025 aims to change this. It is therefore worth examining policies that have accompanied and followed the promulgation of MIC 2025.

First, it is worth looking at China’s long-standing joint venture (JV) law. A longstanding phenomenon in China’s political economy has been that China’s legislative framework has been very generous to Chinese JV partners by legislating transfer requirements directly and indirectly. Indeed, the crux of the matter boils down to the issue of technology transfers in exchange for market access, which has been the focal point of China’s JV policy since the 1980s. One notable part of China’s JV laws is Article 27 of the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of the Import and Export of Technologies, which stipulates that any improvements made to the foreign partner’s technology as part of the work conducted by the JV entity belong to the JV entity (European Commission 2018).

Figure 9.4: OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index: Selected Economies

Source: OECD.

This provision, in addition to several other JV stipulations noted in the European Commission (2018) request for trade consultation with China, gave legal space to Chinese JV partners in order that they could spin off and acquire technology by using Chinese courts to secure their legal rights to said technology. It is therefore notable that this article was removed from China’s JV law by the State Council on 18 March 2020, along with article item 3 of article 43. The latter limited IP protection from transferred technology to 10 years (as opposed to the twenty years typically granted to patent and copyright lifecycles). The new law also removed item 4 of article 43, which required the JV to have the right to use transferred technology by the joint venture after the termination of the period of the technology transfer agreement (Schindler 2019).

The amended law no longer includes paragraph 3 of Article 24, which indemnified the original technology owners in the transfer agreement from third party infringement claims, nor article 29, which limited the range of conditions that the tech transferring party could impose on their Chinese partner that stipulated how this technology is to be used (Schindler 2019). This latter Article stipulated specific conditions on contracts, such as licensing terms, which fall under the category of competition enforcement (State Intellectual Property Office of the People’s Republic of China [SIPO] 2002). Enforcement, of course, remains an open question.

The most salient, but worst documented, change over the past decade and a half has been the declining marginal utility of China’s traditional JV model as a means of technology acquisition, where foreign firms exchanged existing technology for market access. Not only are foreign firms becoming savvier about defending their technology, but China has also moved to integrate the JV model with the broader network of parallel tools of technological catch-up that relies less on importing old technology and more on domestic R&D capacity. It is therefore worth assessing how well China’s JV arrangements in core MIC 2025 technology sectors like semiconductors have helped Chinese firms catch up in localising component supplies.

Semiconductors and Technological Self Sufficiency

State-owned Ziguang/Tsinghua Holdings is a technology commercialisation holding company that owns several semiconductor design, software design and financing firms, including Tsinghua Unigroup (IC design), Tsinghua Tongfang (software), Unisplendour (private equity and investment), Tus Holdings (science parks and incubator) and Tsing Capital (venture capital). This holding company was set up in 2003 by the State Council to separate management and direct ownership of these firms from Tsinghua University, the original owner of Unigroup and Tongfang.

The role of Tsinghua Holdings in China’s semiconductor ecosystem can be understood to have three overarching objectives: (1) investment and commercialisation of R&D; (2) consolidation of China’s IC design industry (consistent with the MIC 2025 goal of seeking to create competitive global enterprises); and (3) attracting foreign partners and domestic state funds to co-develop technology for the Chinese market (Table 9.2). Most notably, Ziguang’s ventures with foreign firms represent the Chinese government’s direct efforts to advance its firms’ positions in the intangible economy. Ziguang, it should be noted, is not itself involved in contract manufacturing, but rather in growing China’s share in the design of integrated circuit (IC) technology and ownership of its underlying IP.

Table 9.2: Tsinghua Holdings’ Sino-Foreign Partnerships

Foreign Firm | Date | Development Type or Product | Total Capital Committed ($USD) | Type of Partnership | Tsinghua Share % |

Hewlett Packard | 2016 | High-end Server Chips | $4.5 Billion | JV: H3C Group | 51 |

Western Digital | 2016 | Data Storage Centres | $300 million | JV: UNIS WDC | 51 |

Intel | 2014– | Cellular phone chip supply | $1.5 billion | JV: Various Ventures | 55 |

ChipMOS and Powertech | 2016 | Various semiconductor design components testing | $235 million | JV: ChipMOS Shanghai | 48 |

Microsoft and 21Vianet Group (domestic) | 2016 | Enterprise data centre for state-owned enterprises | Unclear | Strategic Partnership | N/A |

Affymetric | 2005 | Medical Biochips | Unclear | Strategic Partnership | N/A |

Russia-China Investment Fund, Sistema | 2018 | Precision medicine (biotechnology) | Unclear | Strategic Partnership | N/A |

Dell | 2015 | Cloud computing, Mobile internet, IoT, big data, and smart cities | Unclear | Strategic Partnership | N/A |

IBM | 2015 | Agreement to License OpenPOWER technology ecosystem | N /A | Technology Licensing | N/A |

Sources: Company press releases, Chinese and English language media (cite CIGI paper Malkin 2018).

Ziguang’s Unigroup boasts several joint ventures with foreign firms, as illustrated in Table 9.3. The significance of these JVs is not their novelty—JVs have been a mainstay of China’s FDI regime since the start of Reform and Opening. However, over the past decade, many Sino-Foreign JVs and strategic partnerships, especially in the field of semiconductors have been formed to develop new technology, rather than to import existing technology.

With respect to consolidation, Unigroup, under the leadership of Chairman and CEO Zhao Weiguo (also chairman of Tsinghua Holdings), has undertaken several strategic acquisitions domestically and globally to consolidate China’s domestic chip design capacity and to source global talent and expertise. The firm acquired private semiconductor design firms Spreadtrum and RDA in 2013 and 2014, respectively (see Feng et al. 2019).

In 2014, Unigroup began its partnership with Intel, via the latter’s JV with Spreadtrum. As Zhao put it, “The strategic collaboration between Tsinghua Unigroup and Intel ranges from design and development to marketing and equity investments, which demonstrate Intel’s confidence in the Chinese market and strong commitment to [sic] Chinese semiconductor industry” (Intel 2014). In 2018, Unigroup purchased French chipmaker Linxens (Wu and Chakravarti 2018). These acquisitions coincided with a Unigroup announcement that they would invest $47 billion over five years in their capacity to design high-end chips in China (Cartsen and Lee 2015).

In the same year, China announced the creation of a $31 billion semiconductor government guidance fund, which would use state capital to promote the growth of China’s chip design industry (Patterson 2018). Zhao also then struck a deal with the fund to invest in Unigroup alongside Intel, which would take a 20 per cent stake in newly acquired Spreadtrum (Tan and Yue 2016). In this complex set of cross-investments of Chinese state capital, Ziguang entered into a commercial partnership with foreign firms to develop intangible assets geared towards the Chinese market.

However, as Fuller (2016) argues, Ziguang’s efforts have not been without controversy and have not led to the kind of catching-up in the semiconductor design industry that the government has hoped for. Indeed, what is notable about Ziguang’s experience is the extent to which it illustrates state-owned enterprises’ (SOEs’) focus on the domestic market, and also that top-down political projects have not borne the fruits of self-reliance to the extent that the authorities had hoped (ibid). Indeed, Zhao’s ill-fated attempts to purchase multinational US and Taiwan-based IC champions have been stymied by authorities abroad and were critiqued within Chinese bureaucratic circles as well (Tan and Yue 2016). This illustrates the contradictory nature of MIC 2025’s goals and the need to ultimately adjust the strategy put forward in the plan to achieve the goals of improving China’s position in the global intangible economy and, ultimately, global value chains. Maintaining the goal of self-sufficiency bodes poorly for efforts to upgrade not only China’s manufacturing prowess but also its capacity to create a globally competitive semiconductor sector.

Despite three decades of restricted access for foreign firms and JV requirements for foreign entrance into the market, China’s semiconductor sector remains one of the most foreign-reliant sectors outlined in MIC 2025 (21 Shiji jingji baodao 2019). Impressive as their efforts have been and even with the support of the central government, Ziguang continues to struggle to provide a realistic alternative to domestic technology companies, to say nothing of their ability to compete on the global stage. Moreover, looking at the emerging trends of how Chinese firms acquire foreign technology and at the reasons behind these acquisitions reveals that ramped up technology transfers and direct M&A are less significant aspects of Chinese firms’ competitive efforts than commonly presumed. These changes, documented below, are a product of the development of the intangible economy in China and its integration with the global intangible economy.

The Declining Need for Foreign Technology Assets

What accounts for China’s relatively solid industrial structure, as highlighted in the IMF’s 2019 Article IV consultation? In part, it is the combination of the government’s recent focus on intangible asset development, in combination with Chinese firms’ own global acquisition strategies which are increasingly focused on three aspects of strategic acquisitions: automation and supply chain upgrading; R&D-based acquisitions; and strategic patent plays, which could specifically be described as investments in the freedom to operate in crowded markets. Table 9.1 provides some examples of these strategies and illustrates the importance of the acquisition of IP assets for Chinese firms—indeed, as it does for all competitive global technology firms.

Table 9.1 provides a limited empirical illustration of the logic of MIC 2025. Early critiques and suspicions with respect to MIC 2025 have conflated Chinese firms recent foreign M&A spree, illustrated by high profile acquisitions of German robotics firm Kuka by Chinese appliance retailer Midea Group and the firms’ earlier purchase of Toshiba.[3] Ziguang’s failed acquisition attempts of large US and Taiwanese semiconductor firms only reinforced the beliefs of those that looked at the plan as a thinly-veiled statement of the Chinese government’s intentions to take over global tech and squeeze out foreign competitors, first from China, and then from the rest of the world (see McBride and Chatzky 2019 for an illustration).

However, if we examine developments of China’s intangible economy, outbound M&A trends in the country, and the MIC 2025 document in detail, the role of foreign asset acquisition within the plan becomes far more complex than is typically portrayed. To begin, with respect to the US in particular, China’s outbound M&A activity, especially in high-tech hardware and software sectors has declined steeply since 2017 and has been due in no small part to China’s own actions of tightening capital controls (Hanemann et al. 2019). Not surprisingly, Beijing was unhappy with Zhao’s global acquisition attempts at Ziguang, and the CEO resigned from his position in 2018.

Second, as Table 9.3 shows, understanding China’s outbound tech acquisitions as limited to M&A ignores the logic of intangible asset accumulation and its impact on the strategies of Chinese firms. Simply put, acquiring foreign competitors outright is no longer the only way—or even the most effective—to gain global market share vis-à-vis their foreign competitors. An important tool available to firms in sectors ranging from telecommunications to semiconductors is the acquisition of patents from competitors, which, among other things, give firms greater room to operate and stave off IP infringement lawsuits at home and abroad.

Table 9.3: Selected Intangible Asset-Focused Acquisitions of Overseas Assets by Chinese Firms

Acquiring Firm | Target | Type | Year | Role of Intangibles |

Midea | Kuka (Germany) | M&A | 2016 | Automation and supply chain upgrading |

Toshiba (Japan) | M&A | 2016 | Branding play | |

Geely | Volvo (Sweden) | M&A | 2010 | Branding play |

Ziguang | Linxens (France) | M&A | 2018 | R&D Play |

Huawei | Caliopa NV (Belgium) | M&A | 2013 | R&D Play |

Amartus Ltd-Software Assets (UK) | M&A | 2015 | R&D Play | |

Neul Ltd (UK) | M&A | 2014 | R&D Play | |

Various, including Siemens, Sharp, and IBM | Patent purchases | 2009–2015 | Strategic patent play/ Freedom to operate | |

Xiaomi | Microsoft, Intel, Broadcomm | Patent purchases | 2016 | Strategic patent play/ Freedom to operate |

Sanan Optoelectronics | Sony | Patent purchases | 2017 | Strategic patent play/ Freedom to operate |

Oppo | Dolby, Ericsson | Patent purchases | Strategic patent play/ Freedom to operate | |

Alibaba | IBM | Patent Purchases | 2012 | Strategic patent play/ Freedom to operate |

Source: Thompson-Reuters M&A Database.

As Haskel and Westlake (2018) point out, buying and selling patents is a far more subtle commercial activity than M&A. This is because the value of patents can be quite different for the transaction parties involved. Indeed, the transacting firms do not even need to be in the same industry (see examples in Table 9.3 of Chinese firms purchasing patent portfolios from foreign firms in a range of industries). Rather, patents can fit into firms’ broader technological development strategy, which is in itself an intangible asset—a trade secret. Likewise, firms like Huawei have eschewed (for the most part) large overseas acquisitions and have instead invested in smaller players and in overseas R&D centres, in order to oversee organic growth in the underlying intangible value of these assets.

The MIC 2025 document describes these incentives and processes indirectly. In terms of specifics, these trends are referred to in the State Council’s approach to the rapid degree of automation that is taking place in China’s manufacturing sector. In a sense, automation’s role in the plan illustrates all three aspects of intangible economic activity referred to here: standardisation, balance of payments and asset acquisitions. The document explicitly calls on Chinese policymakers and enterprises to

accelerate the formulation of intelligent manufacturing technology standards, establish and improve the intelligent manufacturing and integration management standards systems […] establish intelligent manufacturing industry alliances and jointly promote intelligent equipment and product development, system integration innovation and industrialisation. Promote the integrated integration of the industrial internet of things, cloud computing, big data in enterprise R&D and design, manufacturing, operation management, sales and service, and the entire industry supply chain (State Council 2015, author’s translation).

Not only does the State Council call for the standardisation of automation and digitisation of the industrial economy, but it also asks Chinese firms to step up and standardise R&D and to commercialise it. Integrating standards effectively implies that firms need to be incentivised to have sufficient IP assets not only to allow for such integration, but also to ensure that such integration accrues revenues to Chinese firms. This would not reduce China’s “dependency” on Western technology because global technological standardisation precludes any one firm (or firms from a single country) monopolising an emerging technology. Rather, if automation and industrial upgrading are more generally likely to balance China’s present-day deficit in intangible payments, Chinese firms need to contribute in greater degree to global technological standardisation and ultimately grab a larger slice of intangible assets, such as patents.

To the extent that intangible asset competition is a zero-sum game where the legal boundaries demarcating the ownership of necessary but exclusive technology are set, even without explicit aims for technological self-sufficiency, the integration of Chinese firms into the global intangible economy will create tensions between China and its trading partners. A narrowing of China’s IP payments deficit not only channels more IPR-related revenues into China’s domestic market, but also increases the West’s dependence on Chinese technology in the same way that Chinese firms are currently dependent on foreign firms. In principle, much as Chinese firms’ dependence on foreign technology is not, in itself problematic, we can conclude that Western firms’ increasing dependence on Chinese firms and their technology might exacerbate cross-border conflict between China and the West, but only insofar as geopolitical tensions dictate. If international tensions can be mitigated and trade tensions are managed there is no reason to presume that a global economy where Chinese firms own more IP and set global technological standards will be significantly different from that which exists today.

Concluding Discussion

This chapter has highlighted a fundamental tension between the globalising and the localising aspects of MIC 2025. It has shown that MIC 2025 displays a deep appreciation for the growing importance of the intangible economy and the need for global competitiveness and global integration associated with this trend. While this chapter has focused on China’s motivations for seeking to attain the goals of MIC 2025, it did not discuss, in detail, the global economic realities which prompt such a policy.

As Schwartz (2017) has shown, the intangible economy relies less on the logic of trade in goods—less on comparative advantage and supply chain-based win-win outcomes—and more on rents accruing from the possession of IP assets like patents. This is especially true for standards-essential patents and trade secrets and other classifications of proprietary technology. The intangible economy, which includes data and standards (hence, the ubiquitous title of “intangible” assets), is not only under-theorised in political science and economics literature, but remains at an exploratory stage from an empirical perspective. But given its centrality to the current US-China trade war, the controversy over Chinese telecom giant Huawei and the ongoing discussion over “forced technology transfers” in China’s JV regime, it is imperative that research across policy-oriented social sciences moves more rapidly in this direction.

It is important to identify appropriate metrics and analytical frameworks for assessing the impact of intangible investment in manufacturing, information technology, green technology and other areas. Specifically, researchers should pay closer attention to the role of asset ownership in the area of standards-essential patents, data and technology clusters such as industrial parks. It has been the intention of this chapter to highlight the importance of studying this data. To assess the successes and failures of MIC 2025 and other industrial policy frameworks in China, more accurate tools are needed to understand how countries ascend global value chains in the context of tightening intellectual property protection and how the growing investment in production networks has been underpinned by an increasing reliance on the industrial internet of things and the growing trade tensions.

To put it another way, it is possible that policies such as MIC 2025 appear to be zero sum because the intangible economy is characterised, to some extent, by zero sum gains vis-à-vis the accumulation of intangible assets by countries, firms, industrial clusters and other public and private entities. But it is also possible that that mutual gains from intangible economic development are not absent, but rather not well understood and poorly represented by the tools that policymakers and researchers rely on to measure economic development and wellbeing. As countries use time-tested policy tools and new measures to stimulate innovation, industrial upgrading and workforce transformation, researchers should use the increasingly available data on patents, standards and other intellectual property assets (proprietary and open source) to refine our understanding of the latest stage of industrial economic development.

Notes

[1] It should be mentioned that the IPRs discussed here do not provide a full exposition of an important segment of China’s intangible economy, namely the role of data ownership and commercialisation. Big data commercialisation is a complex topic that goes beyond the analysis in this chapter.

[2] It should be noted that the OECD FDI Restrictiveness Index measures only formal, regulatory barriers to doing business and various informal barriers as well. National security-related barriers are not sufficiently factored into the final indexes displayed in Figure 9.4. Moreover, while New Zealand is not a major economy by GDP measures, it nonetheless stands out as an OECD member with formal restrictions that nearly match those of China, suggesting that China is neither an outlier, nor can it claim to match the restrictiveness of other middle-income economies.

[3] German media have even referred to the deal as a hostile takeover (see Deutsche Welle 2018). Kuka’s acting CEO at the time of the deal, Till Reuter, explicitly denied this (Hack 2016).

References

21 Shiji jingji baodao [21st Century Business Herald], 2019. “Zhong bang! Zhongguo chanye lian anquan pinggu: Zhongguo zhizao ye chanye lian 60% anquan ke kong, guang ke ji, sheji fangzhen ruanjian cun ‘qia bozi’ duan ban” [Breaking! China’s industrial supply chain security assessment: China’s manufacturing industry supply chain is 60% secure and controllable, lithographic machines, design simulation software fall short, remain in “stranglehold”]. 21 Shiji jingji baodao, 16 Oct. [accessed: 19 Oct. 2019].

Breznitz, Dan and Michael Murphree. 2013. The Rise of China in Technology Standards: New Norms in Old Institutions. US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Riseof

ChinainTechnologyStandards.pdf [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Carsten, Paul and Lee Yimou. 2015. “Exclusive: China’s Tsinghua Unigroup to Invest $47 Billion to Build Chip Empire”, Reuters, 16 November. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-tsinghua-m-a-idUSKCN0T50DU20151116 [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Chen Li. 2014. China’s Centralized Industrial Order: Industrial Reform and the Rise of Centrally Controlled Big Business. New York: Routledge.

Deutsche Welle [DW]. 2018. “German Robot Maker Kuka’s CEO to be Replaced by Chinese Owners”, Deutsche Welle. Available at https://www.dw.com/en/german-robot-maker-kukas-ceo-to-be-replaced-by-chinese-owners/a-46440242 [accessed 15 Oct. 2019].

Ernst, Dieter. 2017. China’s Standard-Essential Patents Challenge: From Latecomer to (Almost) Equal Player? CIGI Special Report. Centre for International Governance Innovation. Available at https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/China%27s%20Patents%20ChallengeWEB.pdf [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

European Commission. 2018. China – Certain Measures on the Transfer of Technology Request for Consultations by the European Union. Available at https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/december/tradoc_157591.12.20%20-%20REV%20consultation%20request%20FINAL.pdf [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Feng Yunhao, Wu Jinxi and He Peng. 2019. “Global M&A and the Development of the IC Industry Ecosystem in China: What Can We Learn from the Case of Tsinghua Unigroup?”, Sustainability 11, 1: 106.

Fuller, Douglas B. 2016. Paper Tigers, Hidden Dragons: Firms and the Political Economy of China’s Technological Development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Girard, Michel. 2019. Big Data Analytics Need Standards to Thrive: What Standards Are and Why They Matter. Centre for International Governance Innovation. CIGI Paper No. 209. Available at https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/Paper%20no.209.pdf [accessed 18 Oct. 2019].

Hack, Jens. 2016. “Kuka’s CEO says Chinese Bidder Could be a Growth Driver”, Reuters. 27 May. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kuka-m-a-midea-group/kukas-ceo-says-chinese-bidder-could-be-a-growth-driver-idUSKCN0YI10K [accessed 28 Aug. 2020].

Hanemann, Thilo, Cassie Gao, Adam Lysenko and Daniel H. Rosen. 2019. Sidelined: US-China Investment in 1H 2019. US-China Investment Project. Rhodium Group and National Committee on U.S.-China Relations. July. Available at https://www.ncuscr.org/sites/default/files/page_attachments/Two-Way-Street-2019-1H-Update_Report.pdf [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Haskel, Jonathan and Stian Westlake. 2018. Capitalism without Capital: the Rise of the Intangible Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hillman, Amy J., Michael C. Withers and Brian J. Collins. 2009. “Resource Dependence Theory: A Review”, Journal of Management 35, 6: 1404–27.

Huang Yukon and Jeremy Smith. 2019. “China’s Record on Intellectual Property Rights Is Getting Better and Better”, Foreign Policy. 16 Oct. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/16/china-intellectual-property-theft-progress/ [accessed 19 Oct. 2019].

Hui Liu and Carl F. Cargill. 2017. Setting Standards for Industry: Comparing the Emerging Chinese Standardization System and the Current US System. East-West Center Policy Studies No. 75. Available at https://www.eastwestcenter.org/system/tdf/private/ps075.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=36156 [accessed 10 Oct. 2019].

IMF [International Monetary Fund]. 2019. People’s Republic of China: 2019 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; Staff Statement and Statement by the Executive Director for China. International Monetary Fund. Country Report No. 19/266. 9 August. Available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2019/08/08/Peoples-Republic-of-China-2019-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-Staff-48576 [accessed 11 Oct. 2019].

Intel. 2014. Intel and Tsinghua Unigroup Collaborate to Accelerate Development and Adoption of Intel-based Mobile Devices. Intel Press Release, 26 Sept. Available at

https://s21.q4cdn.com/600692695/files/doc_news/archive/INTC_News_

2014_9_26_Home.pdf [accessed 10 Aug. 2020].

IPLytics, 2019. Who is Leading the 5G Patent Race? A Patent Landscape Analysis on Declared SEPs and Standards Contributions. Available at https://www.iplytics.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Who-Leads-the-5G-Patent-Race_2019.pdf [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Kennedy, Scott. 2017. The Fat Tech Dragon: Benchmarking China’s Innovation Drive. China Innovation Policy Series. Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Available at https://www.csis.org/analysis/fat-tech-dragon [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Li Y. 2018. Work Report of the China Standardization Expert Committee (CSEC). Standardization Administration of China. Report Summary Presentation [unpublished].

Malkin, Anton. 2018. Made in China 2025 as a Challenge in Global Trade Governance: Analysis and Recommendations. CIGI Paper No. 183. 15 August. Centre for International Governance Innovation.

________. 2020. Getting beyond Forced Technology Transfers: Analysis of and Recommendations on Intangible Economy Governance in China. CIGI Paper No. 239. Centre for International Governance Innovation. Available at https://www.cigionline.org/publications/getting-beyond-forced-technology-transfers-analysis-and-recommendations-intangible [accessed 15 Aug. 2020].

McBride, James and Andrew Chatzky. 2019. Is ‘Made in China 2025’ a Threat to Global Trade? Council on Foreign Relations Backgrounder, 13 May. Available at https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/made-china-2025-threat-global-trade [accessed 20 Aug. 2020].

McKinsey. 2019. China and the World: Inside the Dynamics of a Changing Relationship. McKinsey Global Institute. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/china/china-and-the-world-inside-the-dynamics-of-a-changing-relationship# [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Murphree, Michael and John A. Anderson. 2018. “Countering Overseas Power in Global Value Chains: Information Asymmetries and Subcontracting in the Plastics Industry”, Journal of International Management 24, 2: 123–36.

Murphree, Michael and Dan Breznitz. 2018. “Indigenous Digital Technology Standards for Development: The Case of China”, Journal of International Business Policy 1, 3–4: 234–52.

Neubig, Thomas S. and Sacha Wunsch-Vincent. 2017. A Missing Link in the Analysis of Global Value Chains: Cross-border Flows of Intangible Assets, Taxation and Related Measurement Implications. World Intellectual Property Organization. Economic Research Working Paper No. 37. Available at https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_econstat_wp_37.pdf [accessed 10 Oct. 2019].

OECD. 2020. OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index. OECD.stat. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=FDIINDEX# [accessed 20 Aug. 2020].

Patterson, Allan. 2018. “State-backed Fund Intends to Put China on Semiconductor Manufacturing Map”. EET Asia. 5 March. https://www.eetasia.com/18030505-china-to-set-up-31-5-billion-semiconductor-fund/ [accessed 11 Feb. 2021].

Prud’homme, Dan and Zhang Taolue. 2019. China’s Intellectual Property Regime for Innovation. Cham: Springer.

Reuters. 2019. “Kuka CEO says Midea Offer Not a Hostile Takeover”, Reuters, 18 May. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/midea-kuka-ceo-idUSL5N18F408 [accessed 18 Oct. 2019].

Schindler, Jacob. 2019. “China Budges on Much-maligned Tech Transfer Regulations”, IAM-Media. Available at https://www.iam-media.com/law-policy/china-budges-much-maligned-tech-transfer-regulations [access to subscribers].

Schwartz, Herman Mark. 2017. “Club Goods, Intellectual Property Rights, and Profitability in the Information Economy”, Business and Politics 19, 2: 191–214.

________. 2019. “American Hegemony: Intellectual Property Rights, Dollar Centrality, and Infrastructural Power”, Review of International Political Economy 26, 3: 490–519.

State Council. 2015. Guowuyuan guanyu yinfa “zhongguo zhizao 2025” de tongzhi [State Council Notice on the Promulgation of “Made in China 2025”] State Council Circular No. 28. 19 May. Available at http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-05/19/content_9784.htm [accessed 10 Oct. 2019].

________. 2017. Waishang touzi qiye zhishi chanquan baohu xingdong fang’an [Action Plan for the Protection of Foreign Invested Enterprises’ Intellectual Property]. Available at http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-09/27/5227929/files/

4ebb8148d59c404db6a6f74c6ab539e0.pdf [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

State Intellectual Property Office of the People’s Republic of China [SIPO]. 2002. Regulations on Technology Import and Export Administration of the People’s Republic of China. Available at https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/legislation/details/6585 [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

________. 2015. 2015 Intellectual Property Rights Protection in China. Available at http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?id=141&lib=dbref&SearchKeyword=

&SearchCKeyword=&EncodingName=big5 [accessed 11 Feb. 2021].

Tan Min and Yue Yue. 2016. “Zhao Weiguo de lianjin shu” [Zhao Weiguo’s Alchemy], Caixin wang [Caixin Online]. Available at http://weekly.caixin.com/2016-01-08/ 100897387.html [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

von Hagen, Oliver and Gabriela Alvarez. 2011. The Impacts of Private Standards on Global Value Chains. Literature Review Series on the Impacts of Private Standards, Part I. The International Trade Centre (ITC) Available at https://www.intracen.org/the-impacts-of-private-standards-on-global-value-chains-literature-review-series-on-the-impacts-of-private-standards/ [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Wei Lingling. 2018. “China’s Shrinking Trade Surplus Unlikely to Impress Trump”, Wall Street Journal, 28 July. Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-shrinking-trade-surplus-unlikely-to-impress-trump-1532775603 [accessed 10 Oct. 2020].

WIPO. 2019. WIPO IP Statistics Data Center. WIPO IP Portal. Available at https://www3.wipo.int/ipstats/index.htm?tab=patent&lang=en [accessed 11 Feb. 2021].

World Bank. 2021. “Charges for the Use of Intellectual Property, Payments (BoP, current US$)”, The World Bank: Data. Available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BM.GSR.ROYL.CD [accessed 11 Feb. 2021].

Wu Kane and Prakash Chakravarti. 2018. “Chinese Chipmaker Tsinghua Unigroup to Buy France’s Linxens for $2.6 Billion: Sources”, Reuters, 25 July. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-linxens-m-a-tsinghua-unigroup/chinese-chipmaker

-tsinghua-unigroup-to-buy-frances-linxens-for-2-6-billion-sources-idUSKB

N1KF0B1 [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Wübbeke, Jost et al. 2016. Made in China 2025: The Making of a High-tech Superpower and Consequences for Industrial Countries. Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). Available at www.merics.org/ sites/default/files/2017-09/MPOC_ No.2_MadeinChina2025.pdf [accessed 3 Dec. 2020].

Yu, Peter K. 2018. “When the Chinese Intellectual Property System Hits 35”, Queen Mary Journal of Intellectual Property 8, 1: 3–14.