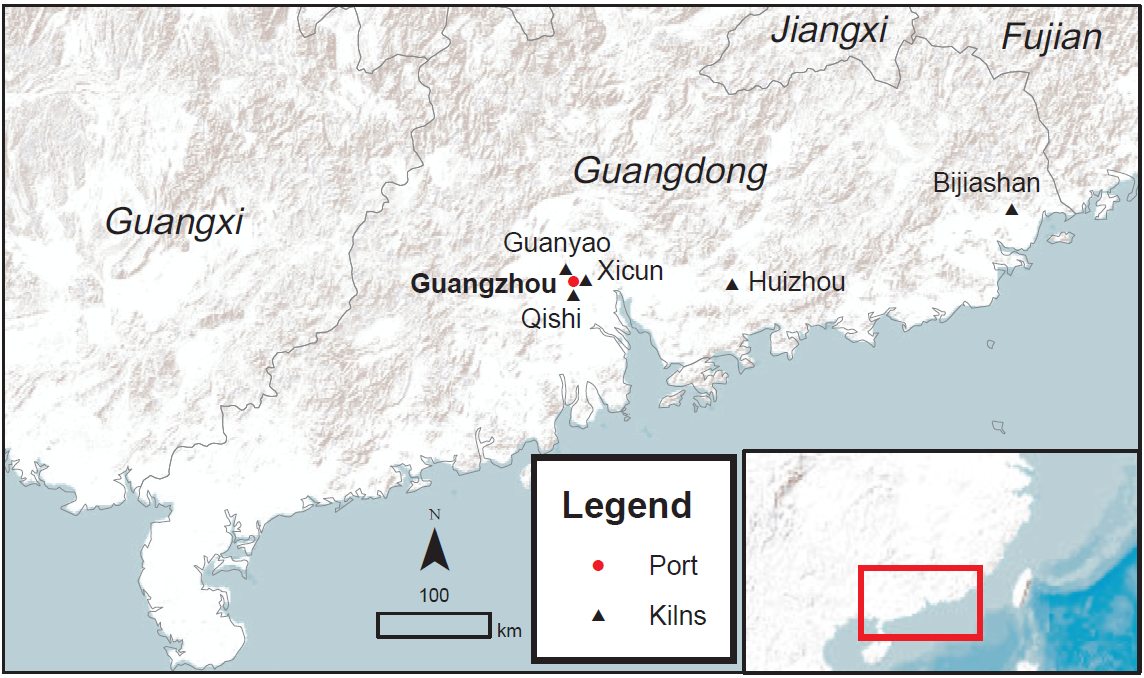

The ceramics cargo of the Lingga Wreck derives exclusively, or almost exclusively, from Guangdong province, China. Ceramic catalogues are often divided by glaze type, which is generally indicative of the site of production. Unfortunately, there is minimal or degraded glaze on many of the Lingga pieces, so apart from obvious categorisations such as painted bowls or temmoku, the various wares have been grouped by shape.

4.1: Painted Bowls

Shallow bowls with an everted rim and an iron-brown painted decoration on the interior come in two typical sizes, approximately 33 cm and 22 cm in diameter. The foot-ring of the larger bowls tends to be better carved than that on the smaller bowls. The decoration is either a simple floral design or in rare exceptions, four cursive Chinese characters which indicate a date, as discussed in detail in Chapter 5 - Dating. Crick (2010: 136) describes the floral design as a branch of chrysanthemums in full bloom. The bowls are covered with an olive green transparent glaze, although in most cases this is now highly degraded. It is continuous to the foot-ring.

This type of painted bowl was made at the Xicun kilns (Guangzhou Committee 1987: 107), located about 5 km northwest of Guangzhou, Guangdong province, although the interior wall of Xicun bowls is usually incised or carved with a scrolling floral decoration. An intact example of this type was excavated in the 10th to 13th century Santubong complex and is now held in the Sarawak Museum. According to Lam (1985: 6), painted bowls without the incised decoration, such as those recovered from the Lingga Wreck, were made at the Nanhai Guanyao kilns, not far from Xicun. A fine example graces the cover of his book, “A Ceramic Legacy of Asia’s Maritime Trade”. It was found on Pulau Tioman, off the east coast of Peninsula Malaysia (Lam 1985: 84), a watering and transhipment stop for vessels following the western route across the South China Sea. Intact bowls of this type have also been found in the Philippines (Brown 1989: 88 Item 4), demonstrating that they were shipped on both the western and eastern routes during the early 12th century.

4.2: Folded-Rim Bowls

The majority of the bowls from the Lingga Wreck have a thickened rim resulting from outward folding. Apart from aesthetics, the thickened mouth-rim is stronger, thereby minimising distortion during firing. These bowls generally have a rounded wall and are relatively shallow. The foot-ring varies in profile from bowl to bowl. Likewise, the colour of the glaze varies from pale green or blue through to white, but invariably stops short of the foot-ring. They are thought to have been made in the Xicun (Guangzhou Committee 1987: 91), Chaozhou Bijiashan (Lau et al. 1985: 117) and Huizhou kilns in Guangdong. Indeed, the wide range of colour and finish suggests a variety of neighbouring or inter-influenced kiln sites. The majority of ceramics on the nearby Pulau Buaya Wreck was also of this type (Ridho 1989: 23). Guangdong folded-rim bowls have been found on Pulau Tioman (Lam 1985: 90), in the Philippines (Brown 1989: 101 Items 71-73), and at Bangko in the middle reaches of the Batanghari River near the Malayu capital, Muara Jambi (Edwards McKinnon 1984).

4.3: Straight-Rim Bowls

The next most abundant ware consists of straight-rim bowls in various sizes. These too vary in shade from white to greyish green, although there are some with a good quality qingbai glaze. Most have a distinct flat well within a carved circular boundary. Bowls of this type were made at a wide range of kilns in Guangdong province.

4.4: Everted-Rim Bowls

There is a range of bowls with everted rims where this feature is barely perceivable in some and in others, severe and flattened. As with the folded-rim, the everted-rim lends strength to minimise warping during firing.

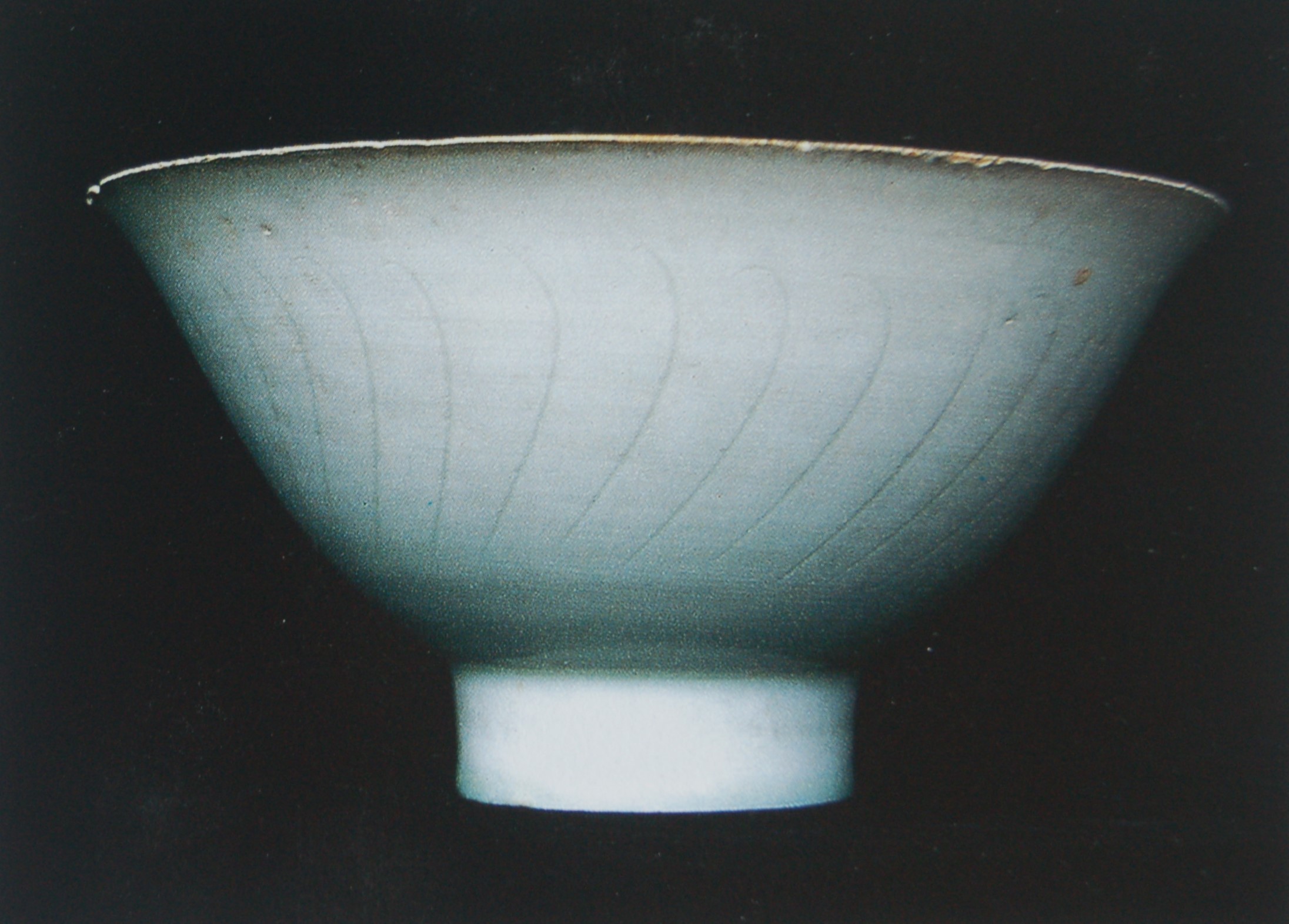

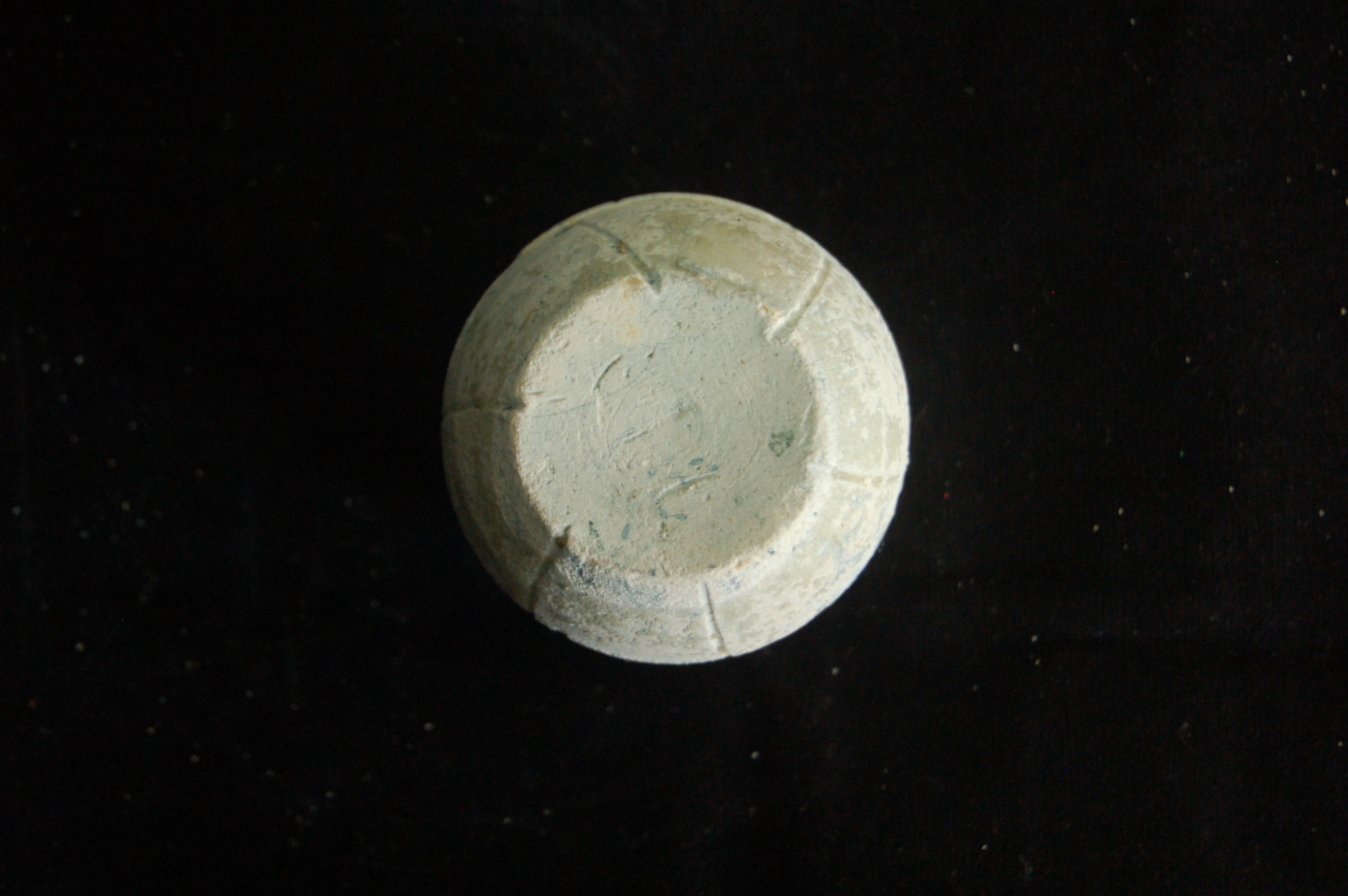

The most common bowls with an everted rim also tend to have a distinct flat well, sometimes within a carved circular boundary. Variations in colour follow the straight-rim bowls. Many everted-rim bowls have carved spiral or ‘S’-shaped striations on the outside wall (Fig. 32), typical of some Xicun wares but perhaps more indicative of Chaozhou Bijiashan production (Koh 2017). Similar pieces have been found at Pulau Tioman (Lam 1985: 89; Lau et al. 1985: 103).

A larger version of the spirally decorated bowl has a distinctive high foot-ring (Fig. 33). It may be compared to a type of bowl recovered from the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Fig. 27). Both have a lightly incised interior decoration, however the Lingga example is not as fine.

A bowl with a well preserved green glaze (Fig. 34) has an incised decoration in the well that is remarkably similar to the decoration on the cover of a covered box (Fig. 29). The covered box is from the Xicun or Chaozhou Bijiashan kilns, so there is a distinct possibility that the bowl came from the same kiln. A fragment of a greenish-yellow glazed jar found in the Bijiashan kilns has the same design (Lau et al. 1985: 96).

4.5: Temmoku

Small black or brown-glazed bowls are referred to as temmoku, the Japanese term for a tea-bowl. The glaze stops unevenly just short of the foot-rim. While these bowls are attractive in their own right, they are a far cry from the famous temmoku made at the Jian kilns in Fujian province. To meet high domestic and overseas demand, Jian temmoku were copied at a wide range of kilns throughout Fujian and in some other provinces. Black and amber-glazed temmoku were made at Chaozhou (Lam 1985: 16; Lau et al. 1985: 117,119) and at Xicun (Guangzhou Committee 1987: 113), both in Guangdong province. However, due to the many kilns producing this ware, it is very difficult to confirm a provenance. A nearly intact example from Pulau Tioman (Lam 1985: 95) has an unglazed rim similar to two types from the Lingga Wreck, and is a possible candidate for the Xicun kilns.

4.6: Covered Boxes

A number of distinctive tall cylindrical covered boxes, which are in several sizes (Figs. 40-41), are products of the Xicun (Guangzhou Committee 1987: 97) or Chaozhou Bijiashan kilns (Lau et al. 1985: 116). They are divided by impressed vertical lines. The smaller variety has rounded covers while the covers of the larger boxes are shaped more like the flower petals. Some are further decorated with incised waves, as discussed above.

Other types are melon shaped (Fig. 42) or cylindrical. A melon-shaped covered box found in the Philippines is similar although finer. Brown attributes it to the Nan’an or Anxi kilns in Fujian province (Brown 1989: 122). The Lingga example is probably from the Chaozhou Bajiashan kilns (Lau et al. 1985: 97).

One decorated covered box with an incised floral decoration on the cover, featuring a pair of peaches in the centre (Fig. 43), is reminiscent of the famous Yue kilns of earlier times.

4.7: Ewers

Crude ewers tend to be squat, with a long, wide and straight neck and a folded mouth rim. A thick strap handle is opposed by a curved spout, with small flattened ear handles in between. A lightly incised ring marks the neck to shoulder junction. A brown or dark greenish-brown glaze stops within a few centimetres of the base, although in most examples it is now difficult to discern the original glaze colour. This type of ewer is typical of the Xicun kilns (Guangzhou Committee 1987: 121). Similar ewers were also recovered from the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Ridho 1989: 47), in in the Philippines (Brown 1989: 98 Item 58).

Far more elegant ewers, some with evidence of a greenish or qingbai glaze, are decorated with incised spirals and lines in much the same manner as the decorated jars (Figs. 61-62), suggesting the same kiln origin. A similar example found in the Philippines is thought to have been made at the Chaozhou Bijiashan kilns in Guangdong (Brown 1989: 95). The neck is narrower than the Lingga ewer, the ear handles are lacking, and the mouth-rim is not flanged. However, it has the same distinctive spiral design on the shoulder. A Yue vase with a dish-shaped mouth from Zhejiang province forms part of the Muller Collection (Crick 2010: 104; Lau et al. 1985: 109). The combed vertical striations are the same as the decorated ewers and jars on the Lingga Wreck, suggesting the origin of this style.

4.8: Vases / Bottles

Pale green-glazed vases are plain or have a series of lightly incised rings around a long tapering neck and a flared cup-like mouth. The foot-ring is also flared. The glaze is badly deteriorated on most examples. They are from the Xicun kilns (Guangzhou Committee 1987: 93) or perhaps from the Chaozhou Bijiashan kilns (Lau et al. 1985: 111; Koh 2017), both in Guangdong province. Similar examples, but with a lobed body, were found on the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Ridho 1989: 39). Other intact examples have been found in the Philippines (Brown 1989: 90 Items 9-13).

A higher quality vase with a transparent green glaze is similar in shape, although the body is less globular and in some cases it is subtly lobed. The rings around the tall tapering neck are carved so deeply that they form flanges. The mouth is elegantly flared, while the foot-ring is near vertical.

4.9: Kendi

Only one kendi was recovered. The spout is missing, however the hole on the shoulder is typical of such breakage and is in the correct position. Furthermore, a similar piece is known from the Philippines (Brown 1989: 108). It has the same lotus decoration, and a dark-brown glaze stopping well short of the base. Brown ascribes it to the Xicun kilns. As does Crick (2010: 76) when describing a similar example in the Muller Collection, although the incised lotus design occurs around the body rather than the shoulder.

4.10: Small-Mouth Jars

There are two types of small-mouth jars. The squat jar with a short neck and with the glaze stopping well short of the flat base was found in quantity. Had the glaze been brown, there would have been a high chance that they derived from the Cizao kilns of Fujian province (Fujian Museum and Jinjiang Museum 2011, Y2), but with evidence of an olive-green glaze, they could just as likely come from a Guangdong kiln. Jars of this type also occur on the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Ridho 1989: 51).

4.11: Basins

Small and medium sized stoneware basins are glazed a dark greenish-brown. The glaze is not applied to the rim, and stops only a quarter of the way down the exterior wall. In many cases there is no remaining evidence of exterior glaze at all. The marks of firing balls on the mouth-rim indicate that the basins were stacked rim-to-rim in the kiln.

The distinguishing feature of these basins is a series of impressed floral or zoomorphic decorations in the interior centre. The base is flat, and in many cases is marked with Chinese characters in ink. These wares are without doubt from the Xicun kilns of Guangdong province (Guangzhou Committee 1987: 121). Again, there are direct parallels with the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Ridho 1989: 37) and with finds on Pulau Tioman (Lam 1985: 101) and in the Philippines (Brown 1989: 110 Items 100-101).

4.12: Wide-Mouth Jars

The smallest wide-mouth jars are lobed. Medium wide-mouth jars have a bulbous body, with little or no neck and a folded mouth-rim. Two to four simple lug-handles are attached high on the shoulder. Some have a rudimentary decoration of incised vertical lines. The brown glaze stops short of the flat base, but in most examples has been eroded away altogether. These utilitarian jars may have been made in at a wide range of Guangdong kilns. Fragments have been found on Pulau Tioman (Lam 1985: 100), while very similar intact examples were recovered from the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Ridho 1989: 51, 59).

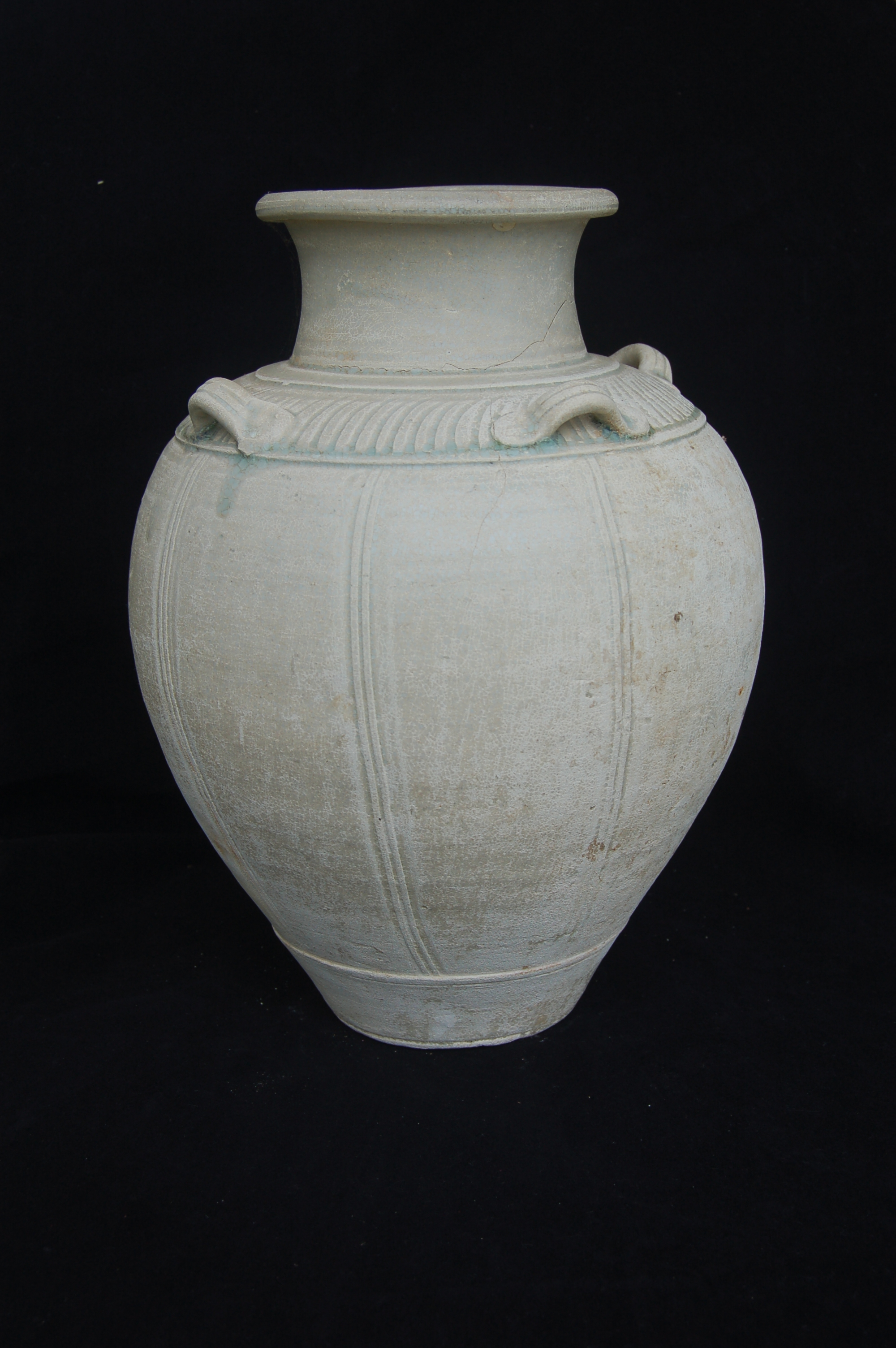

4.13: Decorated Storage Jars

One variety of storage jar is of high quality, with a pale green to qingbai creamy glaze. It has a thick but elegantly everted mouth-rim on a long, gently flaring neck. There are four impressed lug-handles around the shoulder, which is decorated with incised diagonal spirals or petals between horizontal rings. The body is divided into eight panels by vertical couplets or triplets of combed lines that stop short of the base. These jars are identical to jars recovered from the Pulau Buaya Wreck, where they are described as being the first of their kind found in an archaeological context in Indonesia (Ridho 1989: 57). A very similar jar has been found intact in the Philippines (Brown 1989: 107 Item 94), although the shoulder decoration is absent.

4.14: Storage Jars

Many medium sized stoneware jars were recovered from the Lingga Wreck. Some are undecorated. Some have a single wavy line around the shoulder, similar to jars recovered from the early 12th century Flying Fish Wreck (Flecker forthcoming), and to some found on the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Ridho 1989: 55), although the wavy line tends to be below the shoulder on the latter. Most of the jars, however, have impressed decorations on the shoulder between the four lug handles. The decorations are stylised vegetal imprints, either flowers or leaves, and there is great variety.

Most of the jars have lost their glaze although there are remnants showing brown or olive green. From the glaze and decorative imprints they could be from the Xicun kilns where the decorated basins were produced, or more likely the Nanhai Qishi kilns, also in Guangdong, where many jars shards with impressed floral motifs have been found (Koh 2017). Similarly decorated jars have been found on the Pulau Buaya Wreck (Ridho 1989: 55), on Pulau Tioman (Lam 1989: 103-106), and in the Philippines (Brown 1989: 111 Item 102), where one intact examples combines impressed flowers on the shoulder with a wavy line below. Even though the shared decorations imply a common origin, the Lingga storage jars tend to have a longer neck and thicker mouth-rim than the other finds.

4.15: Marks and Inscriptions

As discussed above, there is a wide variety of floral impressions on the storage jars (Fig. 65). One of the basins (Fig. 66) is inscribed with a string of Chinese characters around the base, which interpreted collectively mean “A good person will [naturally] have a good person to look after them, [signed by] Guo Ju-jian” (Dr Tai Yew Seng, personal communication, 2018). An additional cursive inscription occurs on the cavetto of the same basin, the name “Guo” (Mandarin pronunciation), or Kuok (Hokkian pronunciation).

Several ceramics have ink inscriptions on their base, particularly the basins. The inscriptions are typically names and probably indicate the ownership of the ceramics stowed on the ship. These names include Wang, Chen Ba Chang and Weng Pi. In the name, Chen Ba Chang, Ba is the number eight, signifying that he was the eighth child of the Chen family (Dr Tai Yew Seng, personal communication, 2018). From the limited numbers, the inscriptions were probably only written on the bottom bowl or basin within a stack.