Pulau Saigon is not a normal site where one might hope to find stratified deposits that could be interpreted as the result of gradual long-term formation processes such as habitation or artisanal activity. The main formative processes at Pulau Saigon were municipal trash disposal and animal slaughter. The unloading of cargo from bumboats may also have resulted in the haphazard disposal of damaged merchandise. Different types of soil appeared in different locations, probably the result of irregular dumping rather than natural soil formation. Some soil may have been brought here from other parts of Singapore. Barry (2000: 18–21) discusses the complications of interpreting the site.

Artifacts were densely distributed at the site, with the northeastern quarter appearing to exhibit the greatest density. Most of the artifact assemblage was recovered from what was the main river channel, after it had been drained, rather than the island (Barry 2000: 18). Such a site formation model would suggest that the deepest finds would be the oldest, but some recent artifacts such as 20th-century coins were found at depths between two and three meters. The original stratigraphy would have been turned upside down in 1889 when the river was dredged to raise the level of Pulau Saigon. Older items dumped in the river would have ended up on top of the newly elevated surface. There may have been a second period of dredging and filling when the new bridge was built in the 20th century.

Concentrations of similar or identical artifacts took the form of thin horizontal lenses rather than heaps. This suggests that they were thrown into the water from baskets or other containers from the riverbank, or from boats unloading wares to be stored in the godowns. Artifact deposits were found up to a depth of three meters in most areas where excavation reached this depth. In the bed of the river, where coffer dams had been set up to enable excavation, artifacts also were found up to three meters below the surface of the riverbed. These observations show that trash dumping was not confined to the island; trash was also disposed of in the river itself. Casual dumping of trash around the edges of the island declined after municipal trash collection and incineration were introduced in 1889 (Makepeace et al 1921: 325), but obviously did not cease entirely.

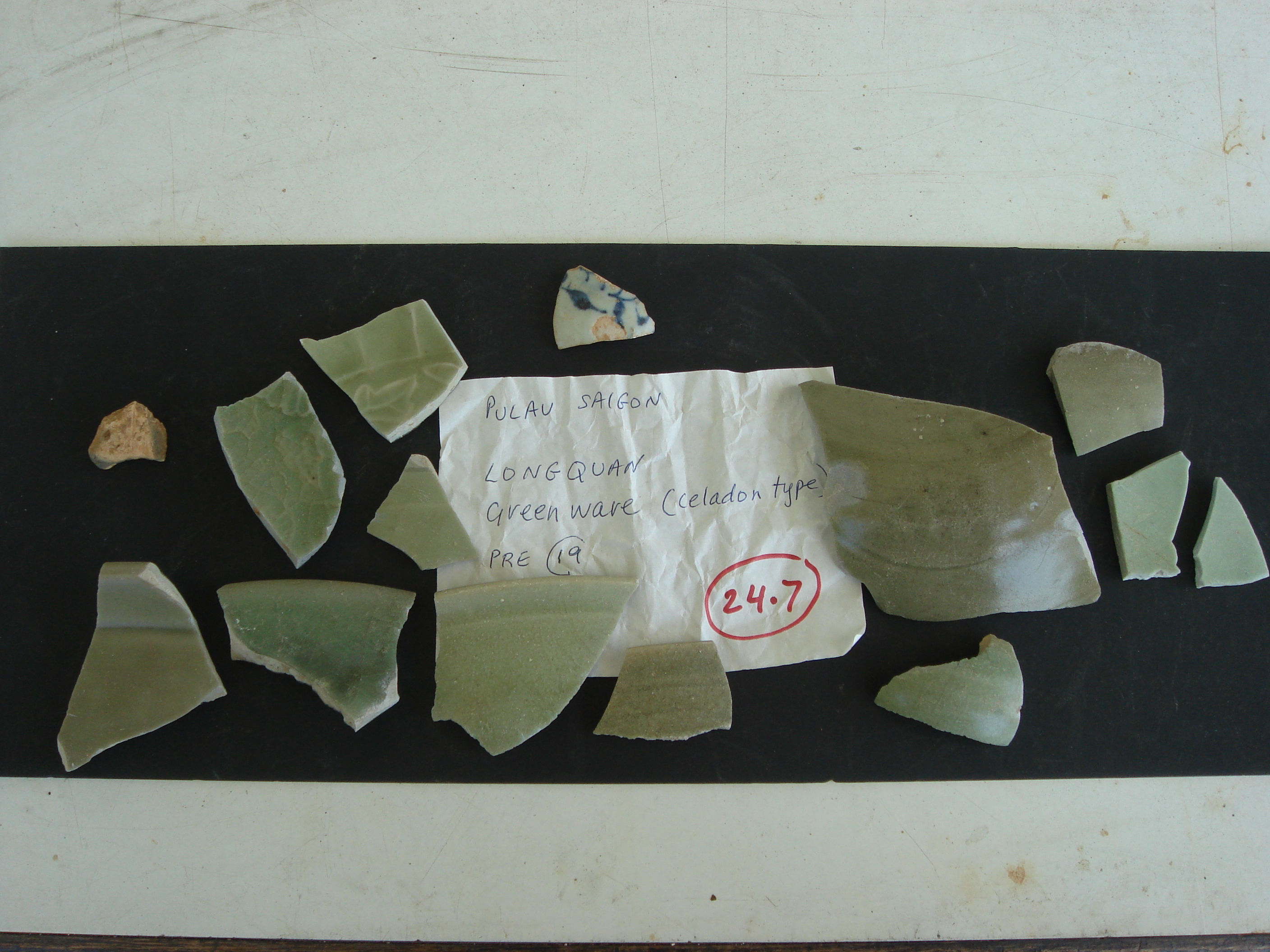

In the eastern arm of the river facing Merchant Road, one of the present authors (Miksic) observed a concentration of almost intact European stoneware bottles. Southwest of Bridge 2 (unnamed bridge on the southeast side of the island no longer extant) in front of the Central Building, conglomerations of black peat and black sandy soil contained a wide variety of materials from shells to flint, slate, fish bone; incised earthenware, coconut shell; coarse glazed stoneware; and Kitchen Qing. This sector also yielded the only clear evidence of precolonial occupation on the island: sherds of several bowls made of 14th-century Yuan Dynasty celadon and one blue and white porcelain sherd.

It is important to note that 14th-century inhabitants who had access to Chinese porcelain lived this far up the Singapore River. No evidence of ancient occupation has been found anywhere on the island this far from the coast.